Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

It’s Been a Long Time

I’ve been incredibly remiss in writing down the fantastic adventures I’ve had working at NASA. I aim to change that.

In my last post (5 years ago!?) I outlined the unlikely chain of events that led to my new career at NASA. At that time I was 20 years into my working career. The door opening at NASA made me feel like I had won the lottery, had achieved the pinnacle of my career. But at the same time, more strongly I felt like I was starting from scratch—had been given a chance to help, to contribute to something important. Being 48 years old at the time I remember thinking with regret that I didn’t have much time left to do this work and I remember realizing what a strange thought that was. How often do people think “oh no, I only have x years left of work before I’ll be retired”? I felt this much more strongly than that I had won the lottery.

That year I worked on three major projects that were interconnected with each other, and I’d like to tell you about them.

1. Apollo 11 on Apollo in Real Time

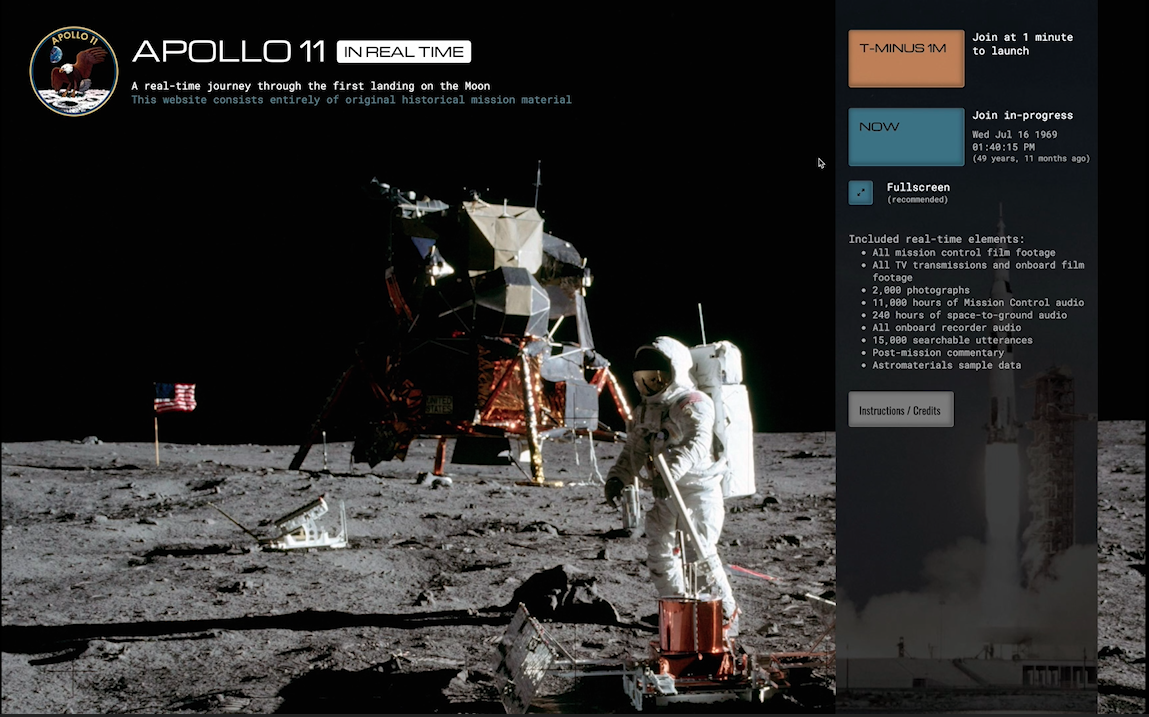

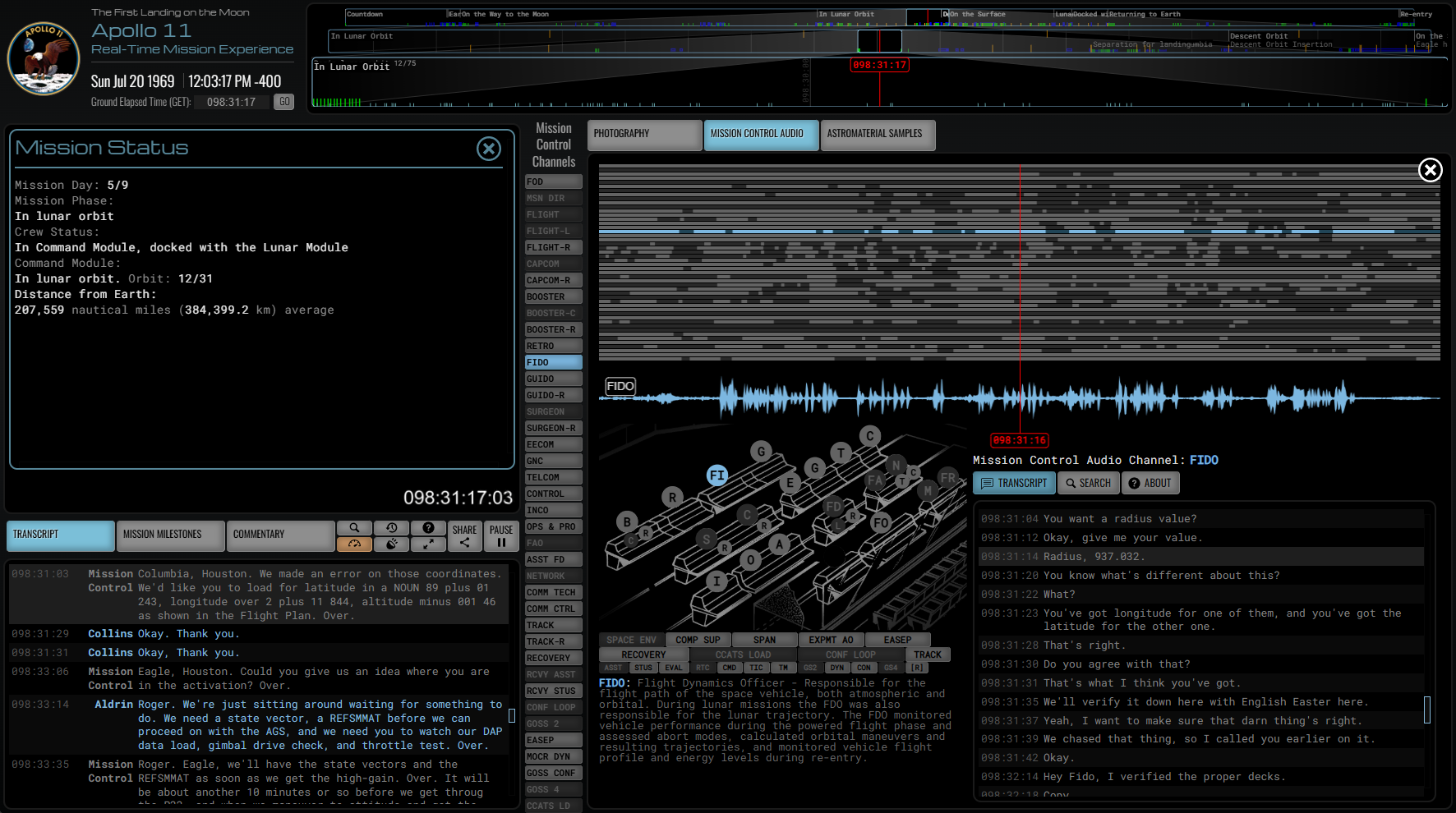

2019 was a peak at the time. The two years leading up to summer of 2019 I had built Apollo in Real Time (AiRT), but this time for the Apollo 11 mission. It was in the same vein as my Apollo 17 solo effort (that had taken me 6 years to make). Now with a small team of volunteers taking up the cause, and the target of having it done by the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 in the summer of 2019, it had only taken us two years to cleanse and time all of the Apollo 11 mission data. We were done by June of 2019 with a soft-launch. It was out in the world and working well. We didn’t know what to expect but I assumed that the Apollo 11 anniversary would be a “big deal” so I beefed up the hosting infrastructure and braced myself for an onslaught of traffic from around the globe.

Apollo 11 on Apollo in Real Time. Open website.

Apollo 11 on Apollo in Real Time. Open website.

Technical Details

Apollo 11 on AiRT was built via a repurposed codebase of the Apollo 17 version, refined for Apollo 11. I made AiRT to have no server-side so that it could be served via CDN with no costly infrastructure. The mission data that would have been provided by a server-side was generated via a series of Python scripts that I run in my local environment, producing flat files for the website to consume via a content delivery network. This works like a charm and results in a blazing fast experience. I continue to be amazed that web browsers can take whatever you throw at them—and I throw a lot at them (more on that later).

30-Track Mission Control Audio

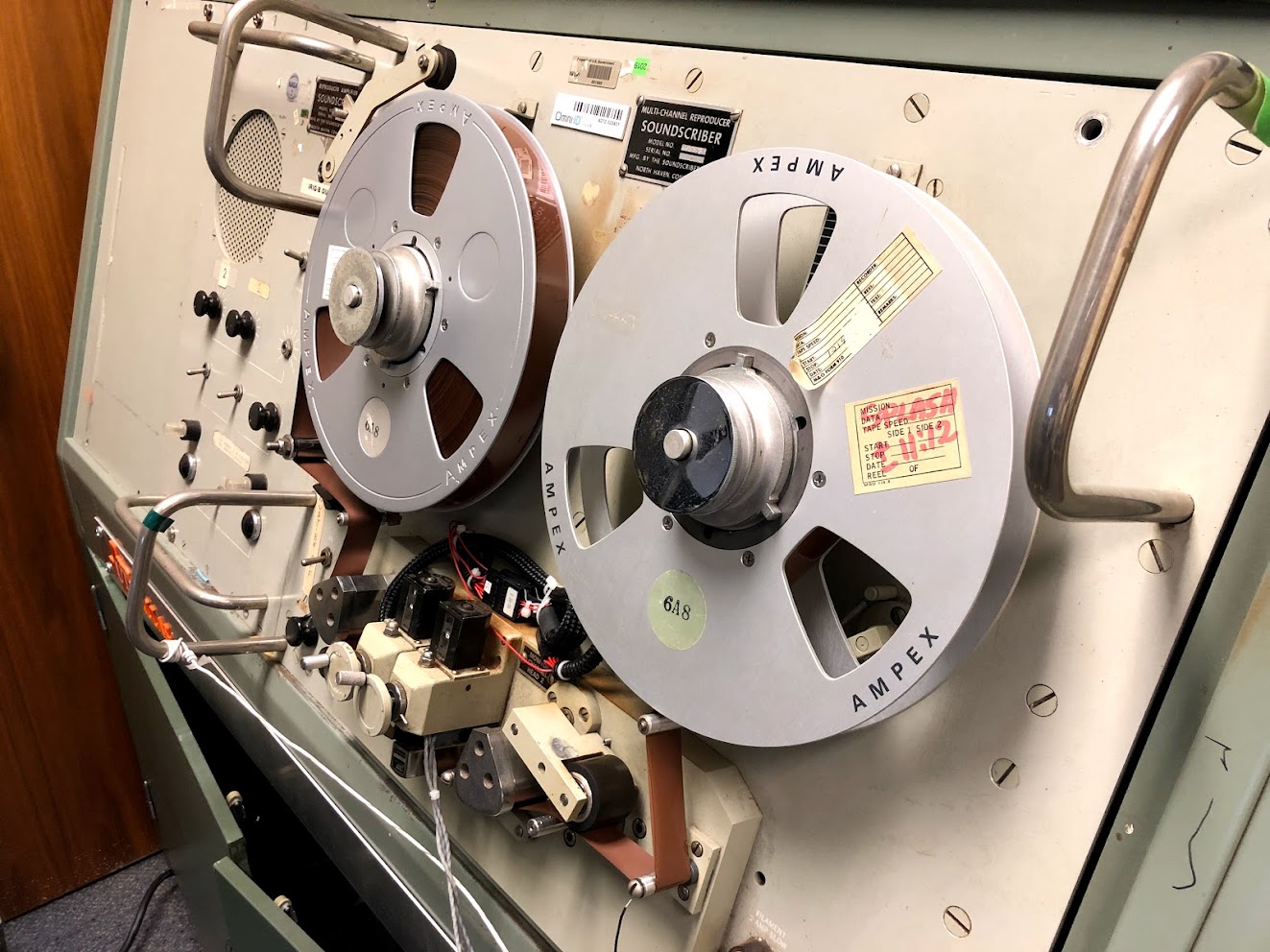

Apollo 11 on AiRT contains 11,000 hours of mission control audio, all placed in context with the rest of the mission. This astoundingly cool historical resource was digitized by John Hansen at the University of Texas at Dallas as part of his linguistics research. There’s only one remaining machine in the world that can play these tapes. It’s in Building 2 at Johnson Space Center (JSC), kept alive by a dedicated team in the Audio Control Room there. The National Archives in College Park, Maryland, house the mission tapes. Discovering these tapes and getting them digitized was a years long endeavor by Hansen and his team. I am forever grateful for his work.

The only remaining machine that can play the 30-track mission control audio tapes.

The only remaining machine that can play the 30-track mission control audio tapes.

I planned to use these recordings for what they are: historical context of the Apollo 11 mission. There was one huge problem: they were 16-hour-long analog tapes digitized on an ancient machine running at the incredibly slow speed of 15/16ths of an inch per second. The digitized files proved impossible to place into historical context because the long-drift speed variations were up to 45 minutes per tape and the short-drift variations were a very noticeable warble at about 3Hz. The tapes didn’t just contain noise that could be processed out with audio software, they were wildly time-distorted and time distortion isn’t something that off-the-shelf audio products are designed to address. I found one or two tools that attempted to handle these kinds of problems but they were completely unable to deal with the 16-hour long tapes.

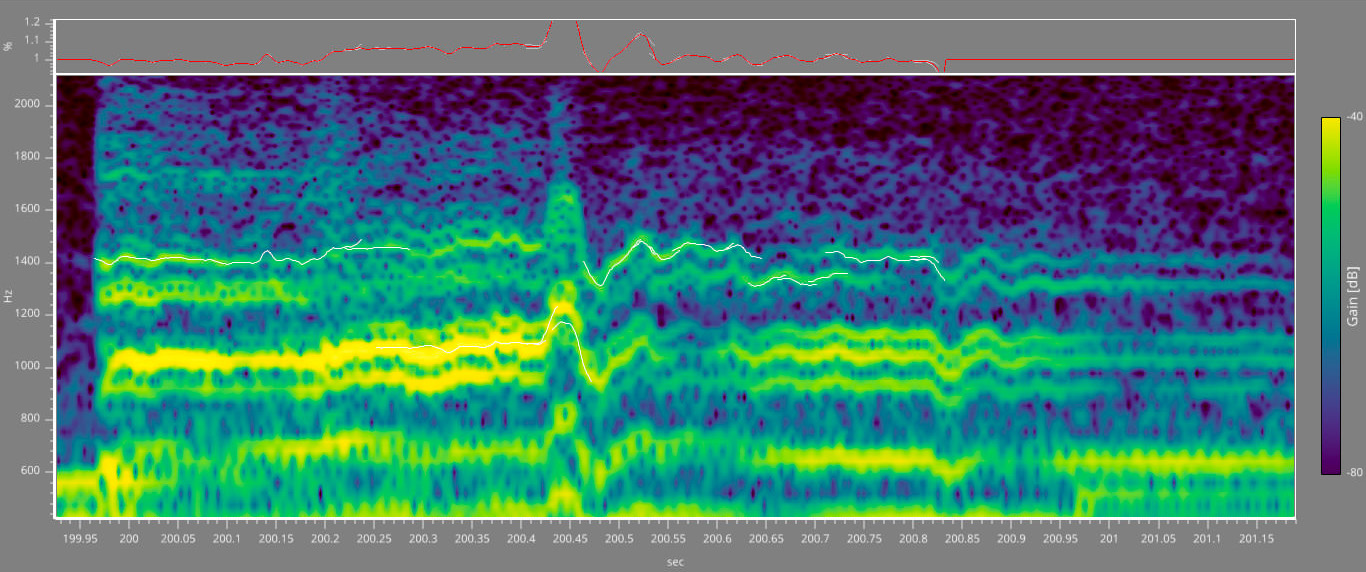

I found a repo online maintained by Arnfinn Holderer, a student in Norway. He had come up with a way to correct time distortions, or “deflutter” audio as long as that audio had a known tone in it. As it happens, the 30-track tapes all included a distorted IRIG-B timecode signal on Track 1. Part of the specification of this timecode signal is a carrier wave at 1kHz. I begged Arnfinn to extend the pipeline in his code to accept 16-hour files and he delivered, on his own time just to be helpful.

Trace of audio flutter distortion fingerprint.

Trace of audio flutter distortion fingerprint.

The result of this script was a fingerprint of the flutter error on track 1, measuring how fast or slow the tape was playing against the known tone for every sample in the audio file. The key breakthrough was that all 30 tracks were recorded simultaneously by Hansen and his team. This meant that if I had the error fingerprint of track 1, I could apply the correction to all adjacent tracks! I did this for the first tape and found that I had reduced the long-drift speed variation to less than 1 second over 16 hours and had entirely removed the 3Hz flutter. The tapes were not only able to be synced into AiRT, they provided a definitive timecode for the entire mission upon which all other materials could be placed in context. The 30-track tapes became the foundational track of Apollo 11 on AiRT. This breakthrough was another reason it only took 2 years to make Apollo 11 for AiRT.

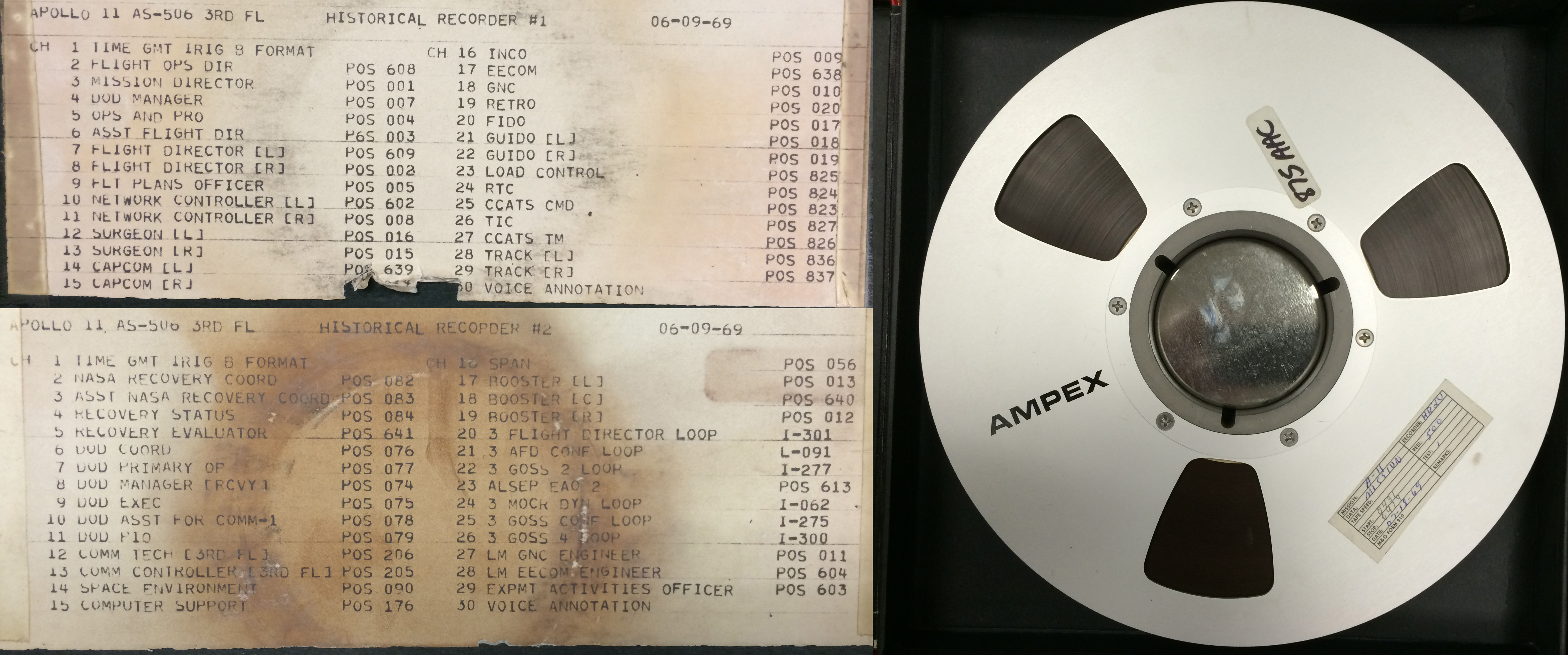

The tracks available on the Apollo 11 30-track mission control audio tapes.

The tracks available on the Apollo 11 30-track mission control audio tapes.

On the AiRT website I made a panel where you can essentially sit in any position in mission control and hear every word spoken on that console’s audio loop. When I first build AiRT for Apollo 17 I wanted to make a deep and wonderful rabbit hole for people to fall into. With this addition to Apollo 11, in spite of the mission being much shorter and containing less photo and video media than Apollo 17, I had made a rabbit hole deeper still. On the Apollo in Real Time Forum, people are still listening through all 11,000 hours of audio on the website and notating the historical significance of what they find.

AiRT Interface to listen to all tracks of mission control audio for the entire mission.

AiRT Interface to listen to all tracks of mission control audio for the entire mission.

Working on AiRT was initially a focused effort to create comprehensive archives of each Apollo mission, driven by a desire to preserve and share this history online. My goal was simply to contribute something meaningful to the internet. Little did I know that this project would open doors to unexpected and exciting opportunities, including a sudden entry into the film industry.

2. Apollo 11 IMAX Film

In 2019 I also worked on the critically acclaimed documentary, Apollo 11 (2019). The path that led to this was an equally unlikely one as my path to working at NASA. In 2015 I got a phone call out of the blue from a film director in NYC named Todd Miller. He had found Apollo 17 in Real Time and called me to say thank-you because he was planning on making a short film about that mission. I joined that film project as a “Technical Consultant” and in 2016, the short film The Last Steps was released at the Montauk Film Festival in Long Island, NY. It was made using only archival material with no narration, endeavoring to let the historical material speak for itself akin to how AiRT does. Todd’s challenge in making this film was much greater than my challenge in making AiRT. I could let the material be boring if it was inherently dull. My job was to place the historical material into context with no narrative regardless of the result. Todd had to make a film palatable to a movie-going audience using only archival material. In short, he did it.

Apollo 11 movie posters.

Apollo 11 movie posters.

Fast forward to 2017 and Todd asked if I would help on another film, this time a feature-length film about Apollo 11. I remember saying to him “I don’t know anything about Apollo 11, I’ve only worked on Apollo 17.” Little did I know how much I would learn. I was also being encouraged by friends at NASA to do Apollo 11 on AiRT in time for the 50th anniversary. That was such a large ask I didn’t know how to say yes, but eventually I did. It wasn’t to be a sanctioned project within NASA. It would have to be another effort of evenings and weekends—all of the evenings and weekends for a couple of years.

When I made the breakthrough on the 30-track audio (described above), I contacted Todd’s producer, Tom and told him “I did it!” meaning that we now had a way to navigate the 11,000 hours of material. Now you could know which console was talking and at what mission time—like a coordinate system of x and y. Plus, the audio didn’t sound terrible anymore with that 3Hz flutter. I sent it all to Tom and he went to work digging through it, helping Todd to weave the narrative of the film out of fragments found in the 30-track audio.

On top of this, my good friend in the UK, Stephen Slater, who was the Archive Producer of the Apollo 11 film project, was attempting to use the 30-track audio for something else altogether. During the mission, two camera operators filmed silent 16mm footage in mission control. They were there to capture b-roll of the events taking place. Because they weren’t recording sound, they weren’t interviewing people or capturing key moments. In fact, it was hard for them to tell what was happening in the room because they weren’t hooked into the mission control audio. This B-roll footage is solid gold. It’s the only record of the events happening in the room when the first landing on the Moon took place. Stephen, using the coordinate system I described above, wanted to add sound to the B-roll.

The Apollo 11 film project had re-scanned all of the 16mm film in 3k (15 - 20 pixels per film grain) and Stephen went to work. In any moment where he could see the lips moving of the people in frame, Stephen identified the individual and therefore what console they worked on, at roughly what time was the clip shot using hints in the room (a display on a console, knowing what shift was on duty by the people in frame, etc.). At that point he narrowed down further by guessing what length of words were being spoken and combing through the defluttered 30-track recordings in Adobe Audition. When he would find a candidate utterance he would attempt to sync it to the lips in the frame. Stephen did this for 18 months and produced 50 different synced clips for Todd to use in the making of Apollo 11. A herculean feat.

One of the clips of silent 16mm film that Stephen Slater painstakingly added 30-track audio to

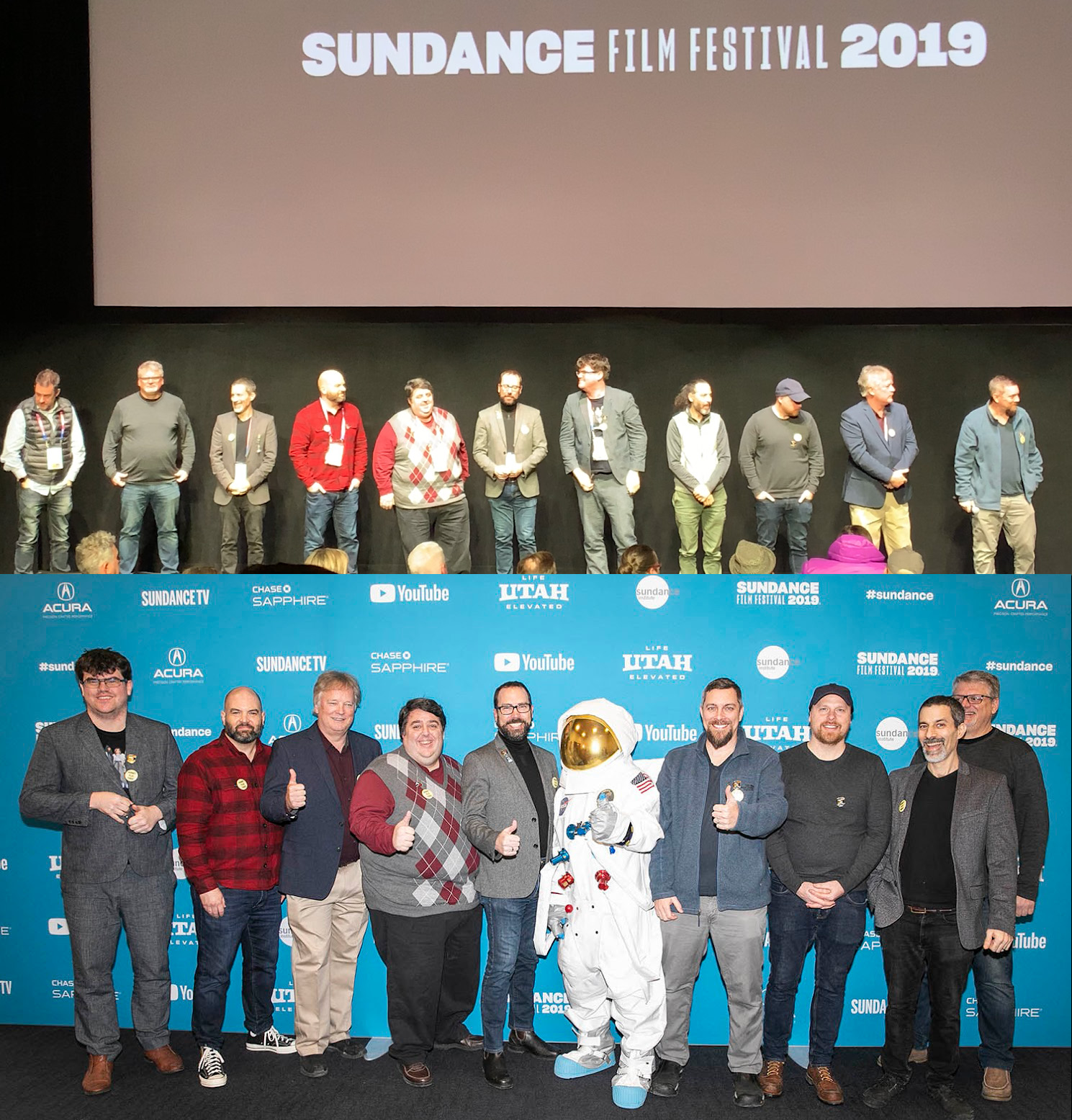

The film premiered at Sundance Film Festival in January of 2019, just as I was hitting reset on my career by joining NASA full time. It won numerous awards and I am super proud to have contributed to it.

Apollo 11 premiered at the Sundance Film Festival where it won the special jury award for editing.

Apollo 11 premiered at the Sundance Film Festival where it won the special jury award for editing.

3. Apollo Mission Control Restoration

Initial Meeting with Gerry Griffin

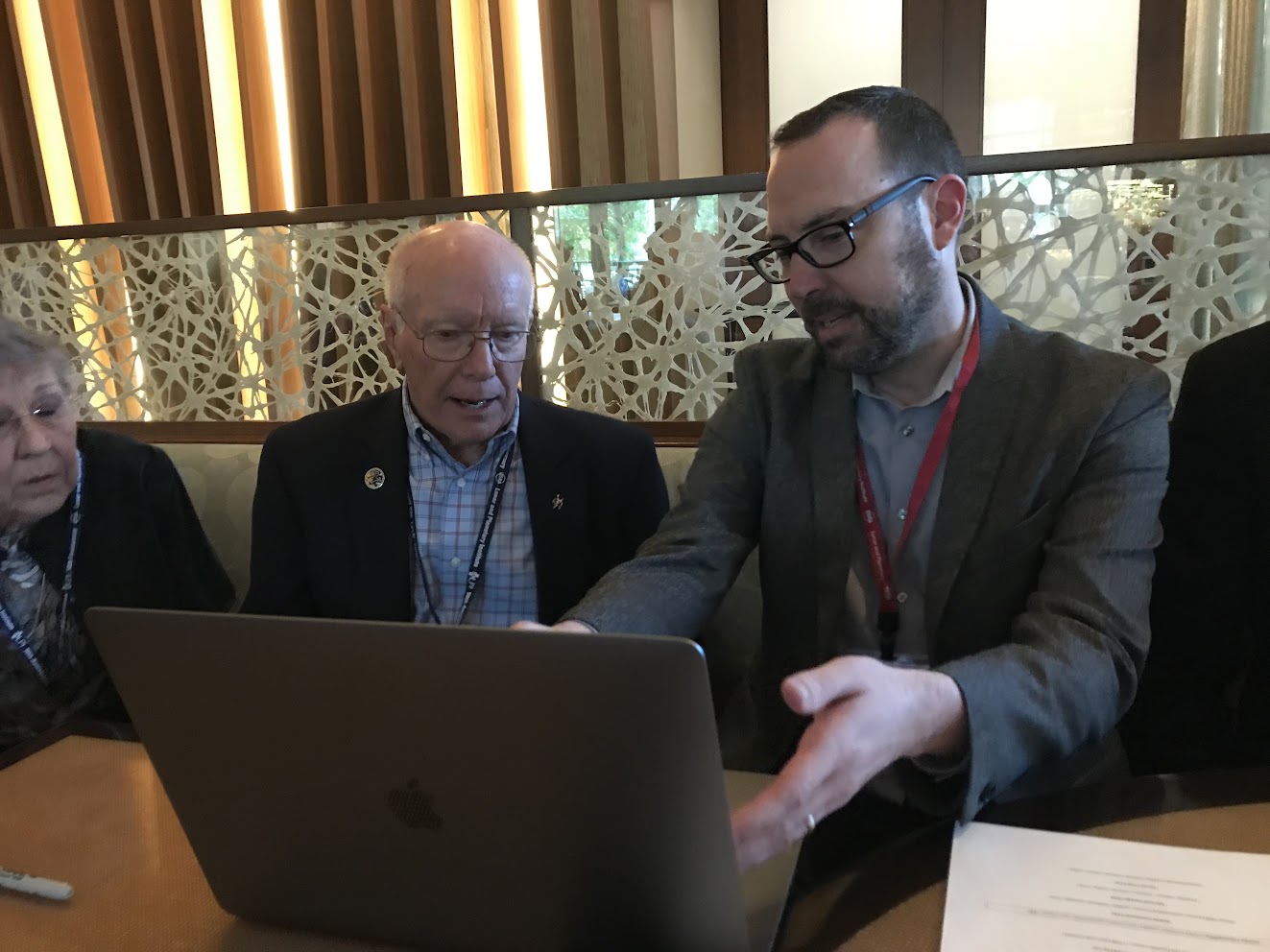

In March, 2018 I had met Apollo Flight Director and JSC Administrator (ret), Gerry Griffin at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Gerry was a fan of my work on Apollo 17 (I was humbled that he had even seen it, but I learned quickly that word spreads fast in the NASA community).

Telling Gerry Griffin about Apollo in Real Time over dinner. Photo by Noah Petro.

Telling Gerry Griffin about Apollo in Real Time over dinner. Photo by Noah Petro.

In summer of 2018 I was invited to JSC to talk about applying my contextual playback approach to current NASA missions. I contacted Gerry Griffin and explained that I had been invited down. He said that if I was going to be at JSC, then I needed to meet Sandra Tetley. Sandra was working on the restoration of the mission control room and Gerry thought that we should know each other.

I emailed Sandra out of the blue and explained that Gerry said we should meet. She didn’t know what the meeting was about and neither did I, but she gave me a time slot.

Days later, I sat outside her offices in Building 45 at NASA JSC feeling overwhelmed in general that I was even at JSC, completely uncertain about meeting Sandra (I’m used to calling meetings when I have something to say). She introduced herself and invited me into her office and apologized for being late. She explained that she had just been with the rest of the Apollo Mission Control Room restoration team and they were all frustrated that there was so little historical material to go on, and they had only a few photos of mission control and old scans of some of the 16mm footage. I laughed and said, “Sandra, you’re going to like this meeting.” I had in my possession all of the re-scanned 16mm footage from the Apollo 11 film project and was in the middle of working on Apollo 11 on AiRT. A partnership was born.

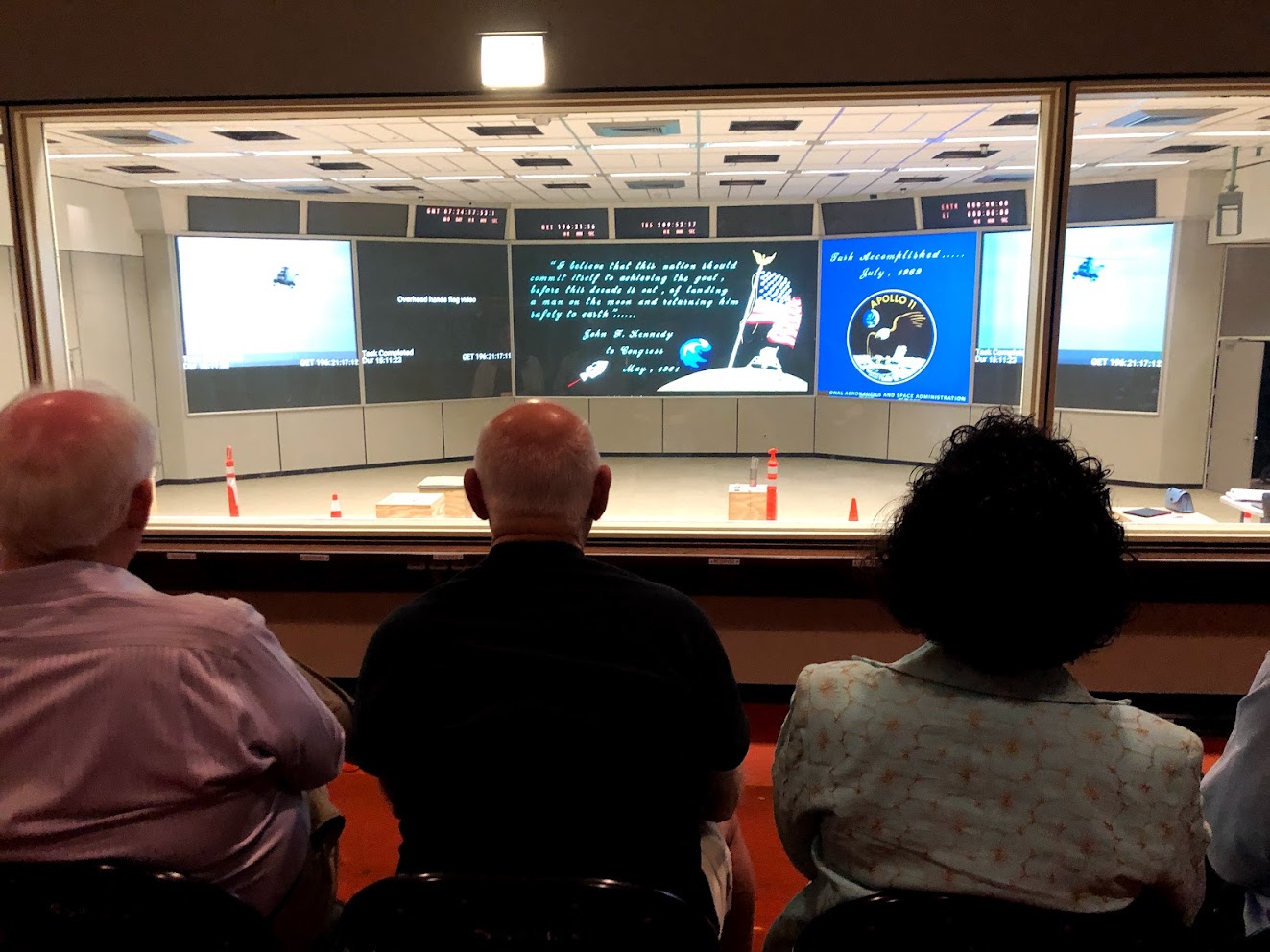

Collaboration with Sandra Tetley

A few months later I was at JSC again as the physical restoration work was nearing completion. The team had shifted their focus to the visitor experience—meaning the presentation that plays when tourists visit the mission control viewing room. It was down to the wire with only months remaining before the ribbon cutting was scheduled (June 2019). I suggested that given that I was in possession of so much material and was working on Apollo 11 on AiRT, why not make the approach for the visitor experience the same? Make it replay mission events exactly as they happened. The room had been painstakingly restored to the greatest historical accuracy down to the smallest detail so making the viewing experience also 100% historically accurate wasn’t a hard sell. My first idea was to place speakers under each of the chairs in mission control and play each track of the 30-track audio through them. It would be like a planetarium; you could go to any point of the mission and the room would come to life with the flight controllers doing their work, spatially in the room. I remember Sandra’s reaction to the idea: “That would be incredible! But there’s no way.” This idea was off the mark. What we needed to make was something that could be shown to several tours per day, was a fixed length, and was easy to play.

Over several hours we broke down what portions of the mission should be in the show. We settled on Landing, the First Step, the Plaque Unveiling, the Call with the President, and Splashdown and Recovery. We’d show only select segments so the total time for the audience would be about 20 minutes. Flight Director, Gene Kranz would act as the show’s host, tieing the scenes together. We had a plan and we all liked it. The discussion switched to getting it all done. We wanted every screen in mission control to show exactly what was on each screen at each stage of the mission. This meant a lot of graphic design and video editing work was needed but the resources weren’t available. I said to Sandra, “If you need help getting this stuff done, I know a guy.” She said, “If you know a guy, I want to be on the phone with him by this afternoon.” And I did know a guy; that guy was Tyler Strahl. Tyler and I had worked together for years and as luck would have it, he had just been laid off from the ever-shrinking advertising industry. I called up Tyler and told him that I had his next gig in hand.

Using historical photography and film footage as reference, Tyler recreated every screen in mission control. In fact, everything you see on the screens when you’re there was created from scratch by Tyler to exacting historical accuracy, right down to the glass plates that were projected on the main board and the hand painted mission recovery slides placed on the screen as the cigars were lit in 1969.

The team working on the visitor experience while the consoles were out for restoration.

The team working on the visitor experience while the consoles were out for restoration.

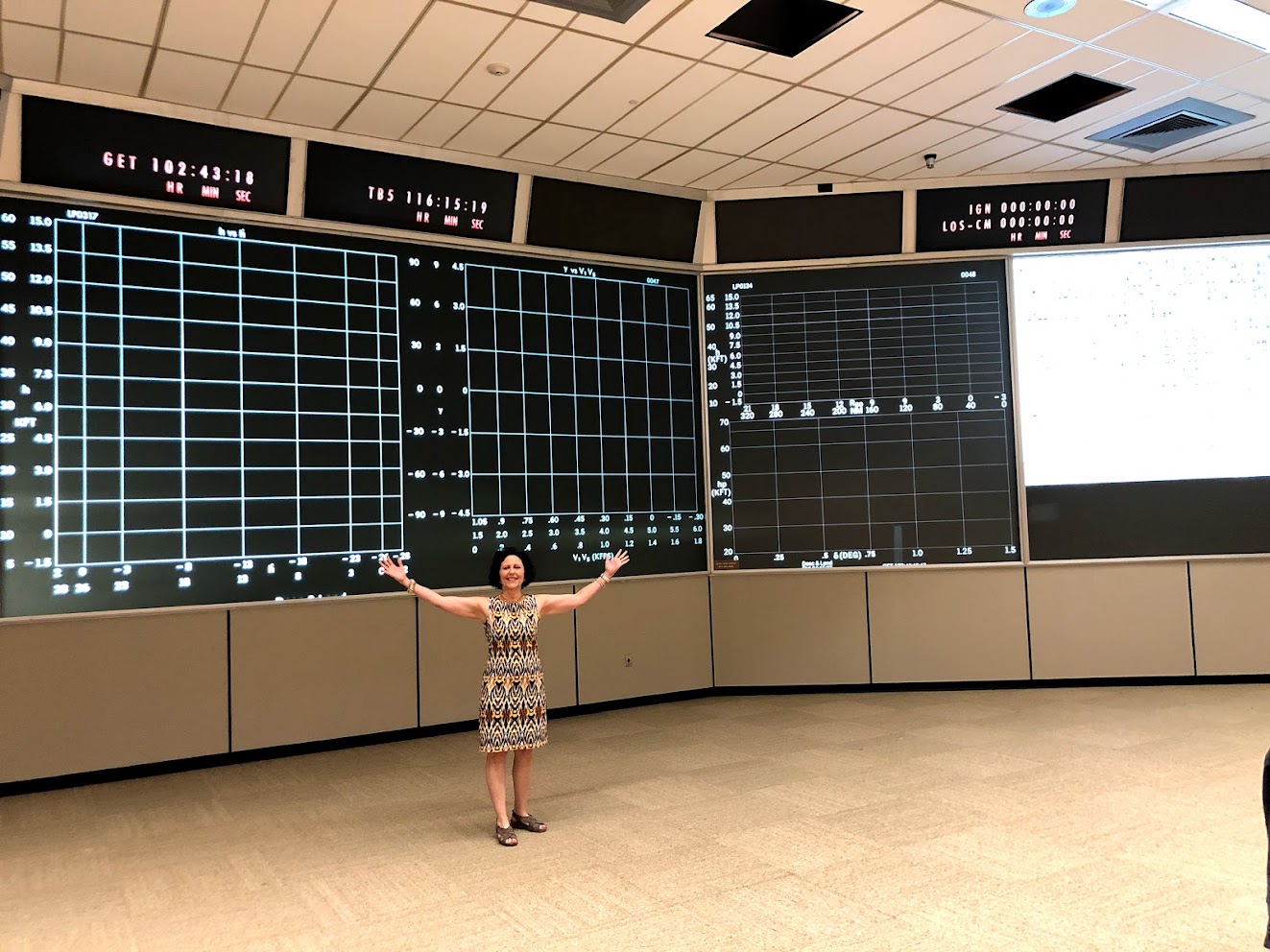

Sandra when we had “first light” of the projection system running our test reels.

Sandra when we had “first light” of the projection system running our test reels.

Tyler Strahl running a live edit of the visitor experience.

Tyler Strahl running a live edit of the visitor experience.

We refined and polished the show and were ready by mid-May, 2019 to show it to Gene Kranz, Ed Fendell, and Spencer Gardner, the people who worked on (and in Kranz’s case, led) the Apollo 11 mission and who raised the funds for the multi-year restoration project.

They didn’t like it.

Mr. Kranz said it lacked emotion, was too long, and generally just wasn’t what he had in mind. I held my ground and explained that that it lacking emotion was the point. It’s 100% historically accurate, without any tinsel added to jazz up the events. The Apollo 11 mission doesn’t need any jazzing up. I felt the power of Gene Kranz’s disapproval cut through me. It was something I’ll never forget. I could see his point though. One only needs to visit a place like the Capitol building in Washington DC and watch that visitor experience to see what Mr. Kranz had in mind. The people in Mission Control were heroes of the highest order and should be celebrated as such—directly. The show we had created didn’t do that, it let the visitors elevate those people to hero status on their own by watching exactly what they did.

Screening the prototype visitor experience for Spencer Gardner, Ed Fendell, and Space Center Houston officials. Stephen Slater is in the foreground.

Screening the prototype visitor experience for Spencer Gardner, Ed Fendell, and Space Center Houston officials. Stephen Slater is in the foreground.

Spencer Gardner, Ed Fendell, and Sandra Tetley watch a test screening.

Spencer Gardner, Ed Fendell, and Sandra Tetley watch a test screening.

We compromised with Kranz and Fendell by agreeing to leave the visitor experience intact and to make a film that was more overt to explain what the people in mission control accomplished, but we would put that film in the lobby area for guests to watch before going upstairs to the historical Mission Control room. A “what you are about to see” kind of thing. The deal was struck and we went ahead to the ribbon cutting with everything intact. Later we heard that the people funding the restoration could not fund the creation of the film in the lobby. I’m still waiting for a call to make that happen.

Months later, Kranz and Fendell came to love the visitor experience. We also polled guests after they’d watched the show. The visitor experience scores a fantastic 98% approval rating.

Fully Restored Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR).

Fully Restored Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR).

On the day we completed the room and the visitor experience, a senior NASA official pulled me aside to thank me. He said that I had been “a gift from God.” I didn’t know how to reply but before I got a chance to say anything he handed me a small box. He asked that I accept this as a token of his appreciation. It was a Flight Operations Directorate challenge coin. I didn’t understand the significance of being given a challenge coin until I mentioned it to my boss later on. “Look what I got today.”, I said as I showed him the coin. “Where did you get that?”, he said with some seriousness. “I got it from the head of Flight Operations.” “I hope you understand how special it is to be given a challenge coin. I have worked here for 30 years and I don’t have one of those.” “Oh.”, I said.

The challenge coin I was given upon completion of the Apollo Mission Control visitor experience.

The challenge coin I was given upon completion of the Apollo Mission Control visitor experience.

The Ribbon Cutting

The blog post I wrote in 2019 about being hired at NASA got some media attention. I’m a dual citizen with both, US and Canadian citizenship and the Canadian media took ownership of me. In June of 2019, The National News on CBC television decided to pursue a story about how my hobby turned into a job at NASA. Eli Glasner was covering the story and asked if he could come to my home office to interview me. I agreed but asked if he could wait a week because I was going to be busy at JSC. “What are you doing at JSC?”, Eli asked. “Believe it or not, I’m participating in the unveiling of the restored Apollo Mission Control room. I worked on it.”, I said. Eli replied, “Great, we’ll fly down for it.” and he did, camera crew in tow.

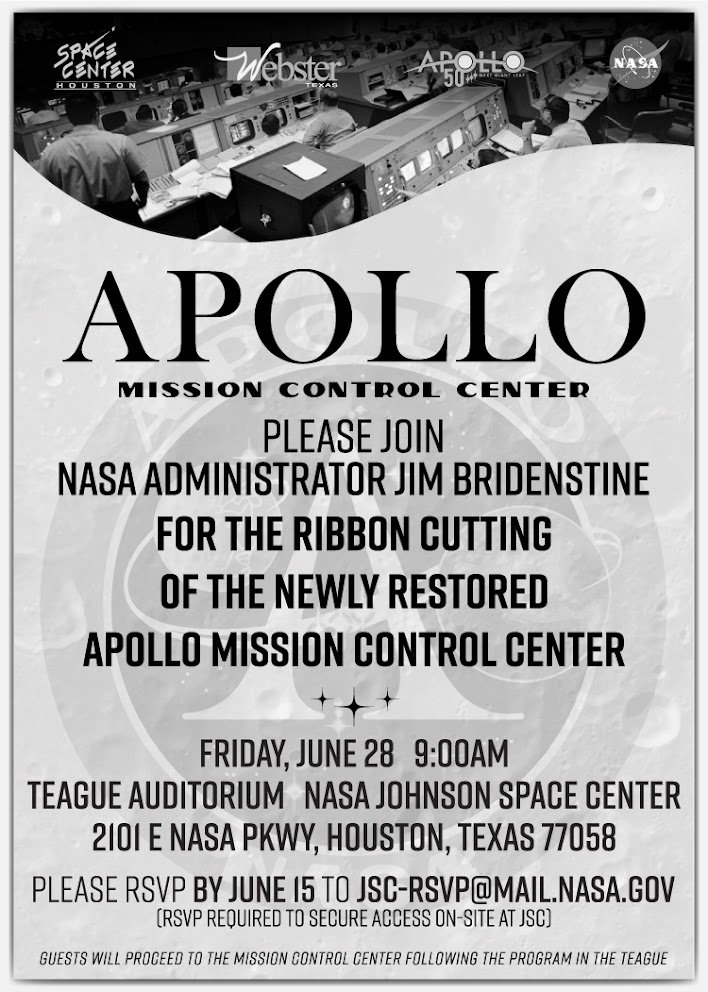

Poster for NASA Staff.

Poster for NASA Staff.

In Houston, media from around the world came for the opening of the Apollo Mission Control room. Gene Kranz was the center of attention. On the media day, he was to give several interviews from the Flight Director chair in the historical room. I was waiting for him with the rest of the restoration team. When he came in, he walked up the side of the consoles and hung up his jacket on a hanger next to the other jackets there. He didn’t notice that all of the other jackets were historical artifacts placed there by the restoration team. He just came to work like it was any other day in 1969, hung up his jacket and headed for his console. We were all elbowing each other with excitement.

As part of the press interviews, all of the flight directors who worked on Apollo 11 were in attendance answering questions. One of the questions was “what is your favorite movie about Apollo?” Many said Apollo 13 (1995), but Glynn Lunney said his favorite was the Apollo 11 IMAX film! I happened to be there with my phone to record the moment.

Spencer Gardner and Glynn Lunney talking to the press. Asked what their favorite movie about Apollo is, they both said the Apollo 11 film!

With the world’s press in the Mission Control room, I stood near the Flight Director console with Eli Glasner and he started asking me questions. I didn’t know I was being formally interviewed at the time, but that was a good thing because I would have tensed up knowing the huge CBC camera was on me. I talked about the importance of Mission Control and how special this particular room is. The interview was aired across Canada that night on The National News. I had had my 15 minutes of fame.

CBC Interviewing me at the Flight Director console. Here’s CBC’s article including this interview

CBC Interviewing me at the Flight Director console. Here’s CBC’s article including this interview

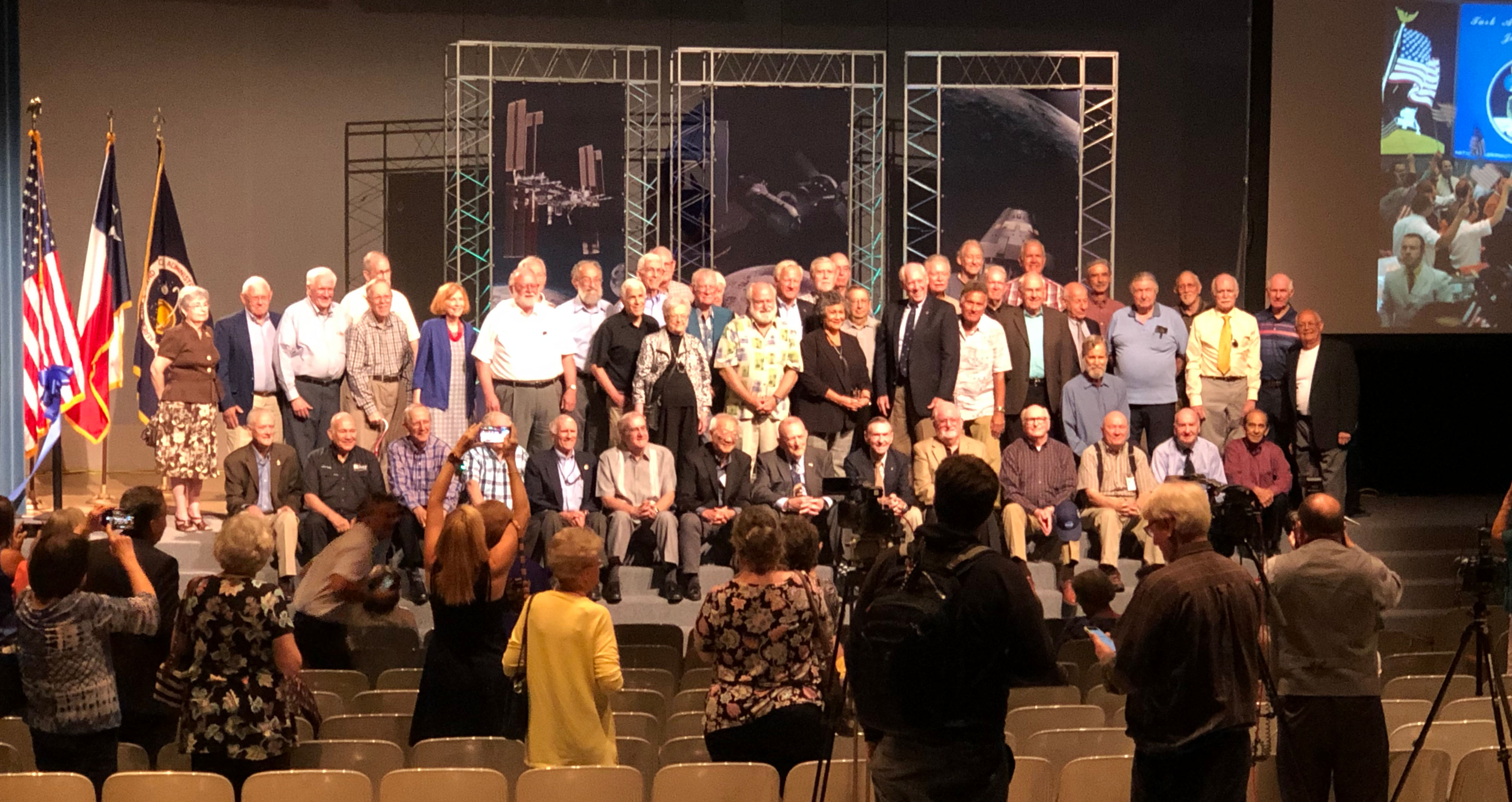

Many of the people who worked in mission control during Apollo gathered in the Teague Auditorium at JSC. Kranz gave a wonderful speech about the heroes who continue to work in mission control. It was only then that I fully let in the importance of the work I had contributed to.

The people who worked in mission control during Apollo, gathered for the reopening.

The people who worked in mission control during Apollo, gathered for the reopening.

Later, all the members of the restoration team received the Governor’s Award for Historic Preservation from the Texas Historical Commission which is proudly displayed on my office wall.

Governor’s Award for Historic Preservation from the Texas Historical Commission.

Governor’s Award for Historic Preservation from the Texas Historical Commission.

The Three Projects Came Together in July 2019 - The Apollo 11 50th Anniversary

Screening Apollo 11 at NASA Goddard

On the anniversary of the day of the launch of Apollo 11, July 16th, I was at Goddard Space Flight Center screening the Apollo 11 film for NASA staff. After each screening I gave a short talk about what it took to make the film. I remember, one of the audience members asked what NASA could do to preserve its current mission data so that it wouldn’t be so difficult for the next generation to do what we had done for Apollo. This is an excellent question that I didn’t have an answer to. Thinking about what the answer might be has led to a lot of the work that I do at NASA today (more on that another time).

Screening the Apollo 11 film at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Screening the Apollo 11 film at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Giving a “making-of” talk after one of the screenings.

Giving a “making-of” talk after one of the screenings.

Screening Apollo 11 at the National Archives

As luck would have it, the Apollo 11 film team was also in Washington DC that week to screen the film for the general staff at the National Archives. The National Archives were the source of all of the large format (and 16mm) film footage that the film was comprised of. After the film. Todd and his team gave a Q&A and presented the National Archives with the award he was given at the Sundance Film Festival where the film was premiered. He said that the National Archives deserved the award more than anyone else, because without their hard work, we wouldn’t have had these historical treasures.

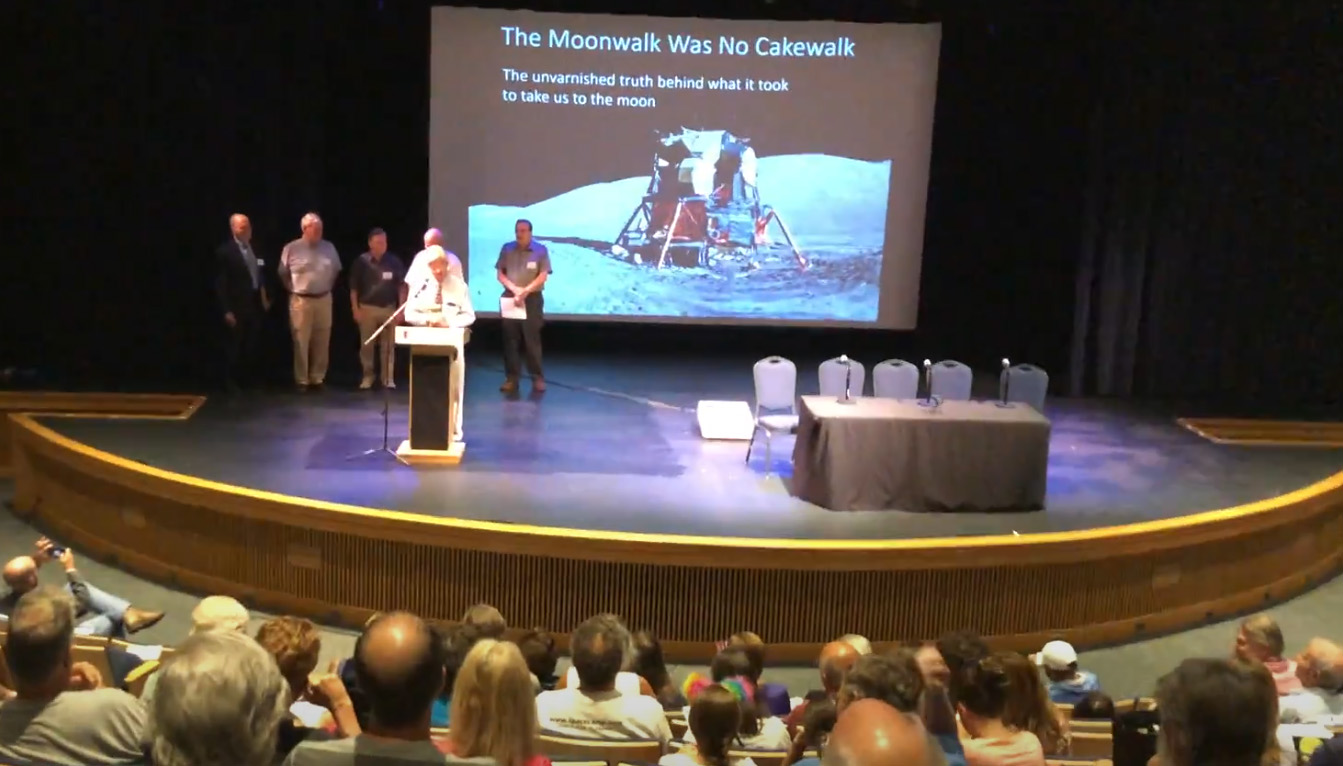

Heading to Long Island to Preset to Grumman Retirees

The next day I flew to Long Island, NY. I had been invited to be there on July 20th to give a talk and screen the Apollo 11 film for some of the retired Grumman engineers and managers, who had built the Apollo Lunar Module spacecraft. The screening of the film, just by coincidence, was timed so that in the film when the lunar landing occurred, it happened at exactly 50 years after the actual landing. I had the privilege of spending some time with the Grumman workers after the event. Their eyes were still bright with excitement when they talked about the mission and they were very grateful to the Apollo 11 IMAX film team for doing their mission justice.

Retired members of the Grumman team who built the Lunar Module giving a joint presentation at The Montauk Observatory, Long Island, NY.

Retired members of the Grumman team who built the Lunar Module giving a joint presentation at The Montauk Observatory, Long Island, NY.

Anniversary of Apollo 11 Recovery on the USS Hornet

On July 24th I was at NASA AMES Research Center in Silicon Valley to give a presentation at the NASA Exploration Science Forum, a conference hosted by NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SSERVI). After the conference proceedings ended, we all went to the USS Hornet, now a museum in Alameda, California, for a special event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the USS Hornet’s recovery of the Apollo 11 Command Module from the Pacific Ocean.

My presentation at the NASA Exploration Science Forum.

USS Hornet on the 50th anniversary of the recovery of Apollo 11.

USS Hornet on the 50th anniversary of the recovery of Apollo 11.

Before the event I asked the SSERVI organizers if we could give the Hornet a gift. I had in my possession, the ship-to-shore communications throughout the mission that I recovered from the 30-track audio tapes. At the start of the ceremony I handed the museum director a USB stick that contained these recordings for the museum to keep with their other historical material. It was a moment I’ll never forget.

The discussion panel on stage below deck on the Hornet. Jake Bleacher, NASA Chief Exploration Scientist is at the podium and Jack Schmitt, Apollo 17 Lunar Module Pilot, is seated on the panel with other scientists.

The discussion panel on stage below deck on the Hornet. Jake Bleacher, NASA Chief Exploration Scientist is at the podium and Jack Schmitt, Apollo 17 Lunar Module Pilot, is seated on the panel with other scientists.

Jack Schmitt, Apollo 17 Lunar Module Pilot and myself, in the audience.

Jack Schmitt, Apollo 17 Lunar Module Pilot and myself, in the audience.

Apollo in Real Time Gets Global Attention

When the anniversary hit AiRT, everything I had been working on for years came to a head. Over 1.1M people from 224 different countries watched AiRT in “real time”. Hosting the website via a content delivery network saved my bacon. It cost me some money in hosting fees, but the website stayed online under the onslaught of traffic. To make matters even more complicated, I was monitoring the site traffic while on the road in Washington DC, Long Island, and California.

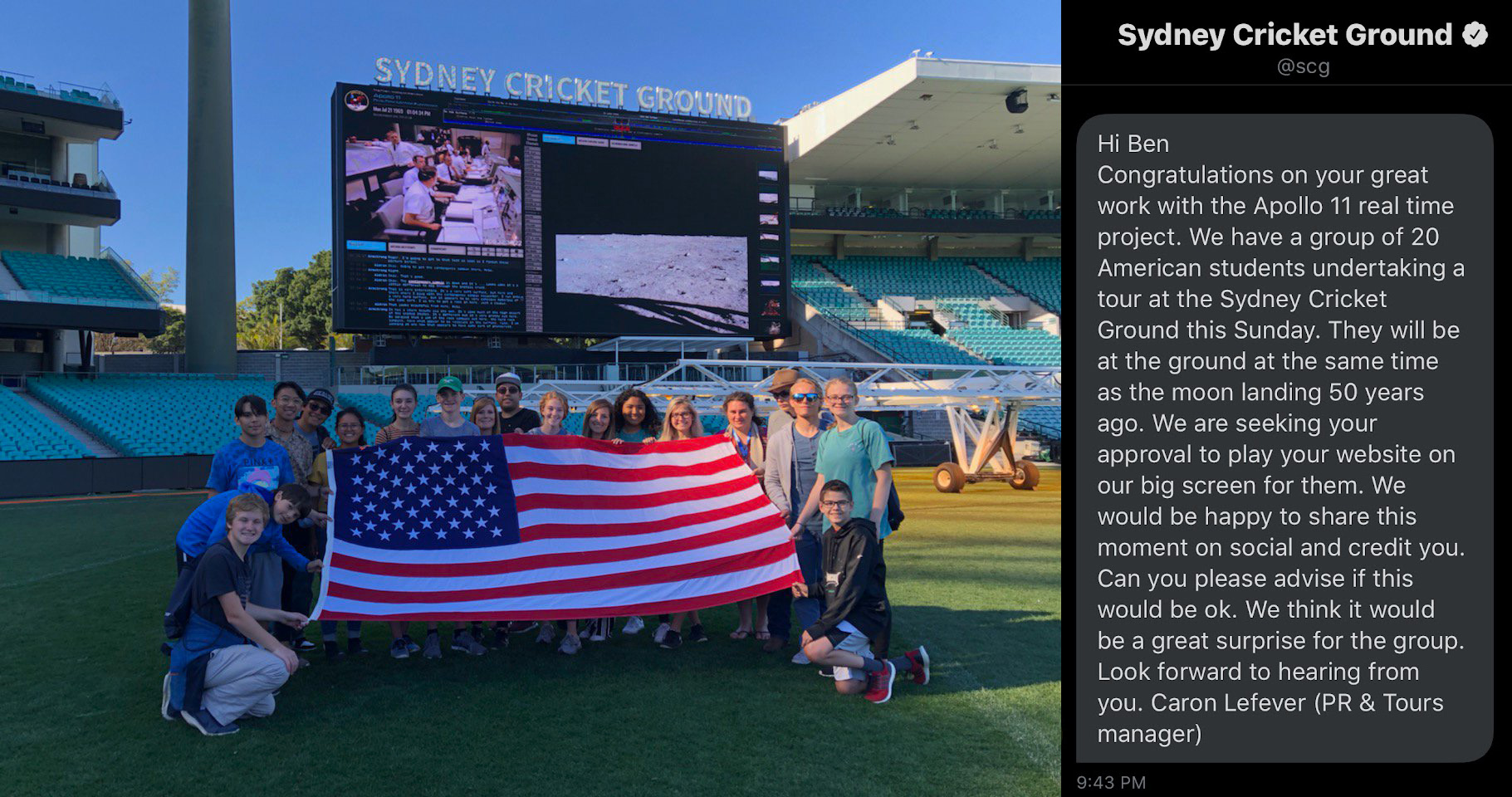

Leading up to the anniversary I was contacted by many organizations, from planetariums to sports stadiums, across the world asking for permission to use AiRT as part of their Apollo 11 anniversary celebrations. I always granted permission and never charged a fee. I only asked that they send me photos from their event.

Celebrating Apollo 11 anniversary in Sydney Australia.

Celebrating Apollo 11 anniversary in Sydney Australia.

I woke up on July 21st to this in my Instagram feed. Brian May had brought up Apollo in Real Time during his concert in Los Angeles.

Case Study Video

This case study video shows the global impact of Apollo 11 on Apollo in Real Time.

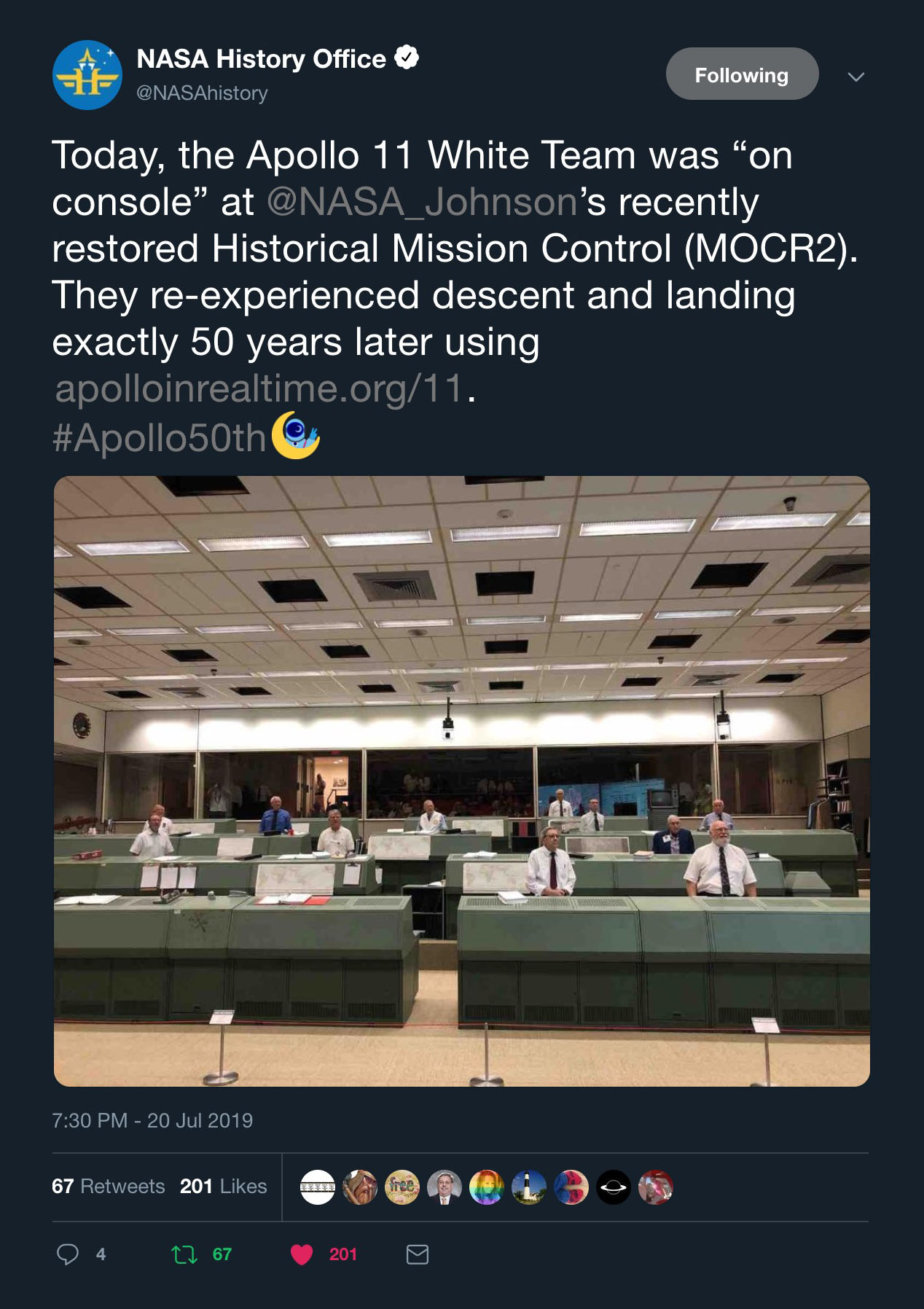

Apollo in Real Time in Apollo Mission Control

During the Long Island screening I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. It was my friend Adam Graves, one of the key contributors to the Apollo Mission Control restoration. He said that JSC was running an event to commemorate the 50th anniversary of descent and landing. The surviving flight controllers who were on shift during descent and landing were back at their console positions for a photo op. Adam was standing at the front of the room and took the opportunity to open AiRT on his phone and turn the volume up. Everyone in the room fell silent and listened. They listened to themselves doing their jobs during descent and landing, exactly 50 years later.

I couldn’t believe it when Adam told me what he had done. I wish I had been there, but I’ll settle for this tweet from the NASA History Office.

NASA’s tweet about the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s descent and landing.

NASA’s tweet about the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s descent and landing.

New Opportunities at NASA Johnson Space Center

During a staff meeting of the Extravehicular Activity (EVA) flight controllers (the people who train astronauts how to conduct space walks and work in mission control during space walks), the head of the EVA branch brought up Apollo in Real Time during the anniversary to show the staff. Luckily, one of the flight controllers in the room knew me and said, “That guy works here!” Later, the branch chief reached out to me and invited me to be his guest in mission control during the next EVA (space walk).

In August 2019, as the EVA branch chief’s guest, I was in the active Space Station Mission Control, one floor below the Apollo Mission Control room, watching an EVA. As we got to talking, I explained that I was working on making “Neutral Buoyancy Lab in Real Time”. He thought that was great but asked why I was only doing it for the NBL and not for the Space Station itself. I said I thought that I had to prove the concept at the NBL before I could do anything like that. He said that NBL would be great and all, but what the flight control community really needed was a system that would essentially be “ISS in Real Time”. So I started building an application to do just that; but I’ll save the details of that for another time.

In mission control, watching an EVA. Flight controllers brought up Apollo in Real Time on their console.

In mission control, watching an EVA. Flight controllers brought up Apollo in Real Time on their console.

Giving Talks Everywhere

For the remainder of 2019 I was on the road giving talks. I was invited as a special technical speaker to Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, AL. I spoke to the public outreach team at Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA. I spoke at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. I also conducted several private speaking engagements for organizations interested in my work. It seems that people find my story inspiring and want to hear about how a personal passion project led to this crazy new work life.

Setting up for my talk at JPL in California.

Setting up for my talk at JPL in California.

Reflecting on 2019, the convergence of these three major projects not only transformed my career but also contributed significantly to the legacy of Apollo 11. After the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 had passed, I started my new job as a software engineer at NASA in ernest. I knew that I had to strike while the iron was hot and demonstrate what I was capable of. I couldn’t just be the person “who made that cool website about Apollo” for long. In my next entry I’ll talk about my first big NASA project. I hit it hard with everything I had.