Hello, I write software at NASA Johnson Space Center for Mission Control and the broader scientific community on the ISS and Artemis missions.

Getting to do this work has been a wonderful adventure. I hope you find something here that you enjoy.

Hello, I write software at NASA Johnson Space Center for Mission Control and the broader scientific community on the ISS and Artemis missions.

Getting to do this work has been a wonderful adventure. I hope you find something here that you enjoy.

In 2019, three major projects came together: Apollo in Real Time for Apollo 11, the Apollo 11 IMAX documentary, and the restoration of NASA’s Apollo Mission Control room. Here I talk about the confluence of these three opportunities hitting at once and the adventures that ensued.

A personal journey from working on Apollo 17 historical data to being recruited to work at NASA, Johnson Space Center, detailing the experiences and milestones along the way.

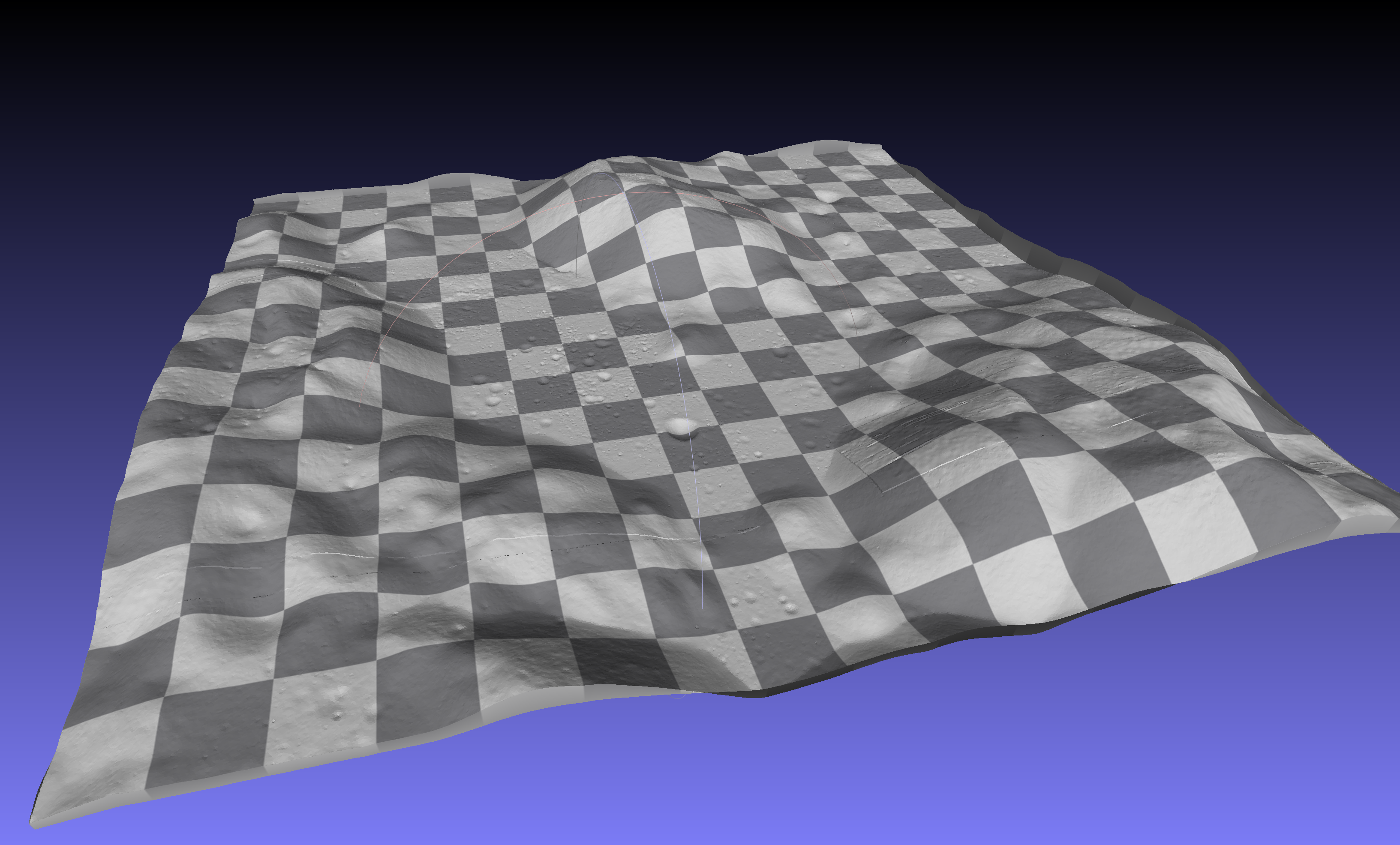

Creation of a 3D simulation of Apollo 17's landing site using high-resolution data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, combined with mission audio and visual archives. Highlights innovative techniques to recreate the lunar surface and astronaut activities with unprecedented accuracy for the 44th anniversary of the Apollo 17 mission.

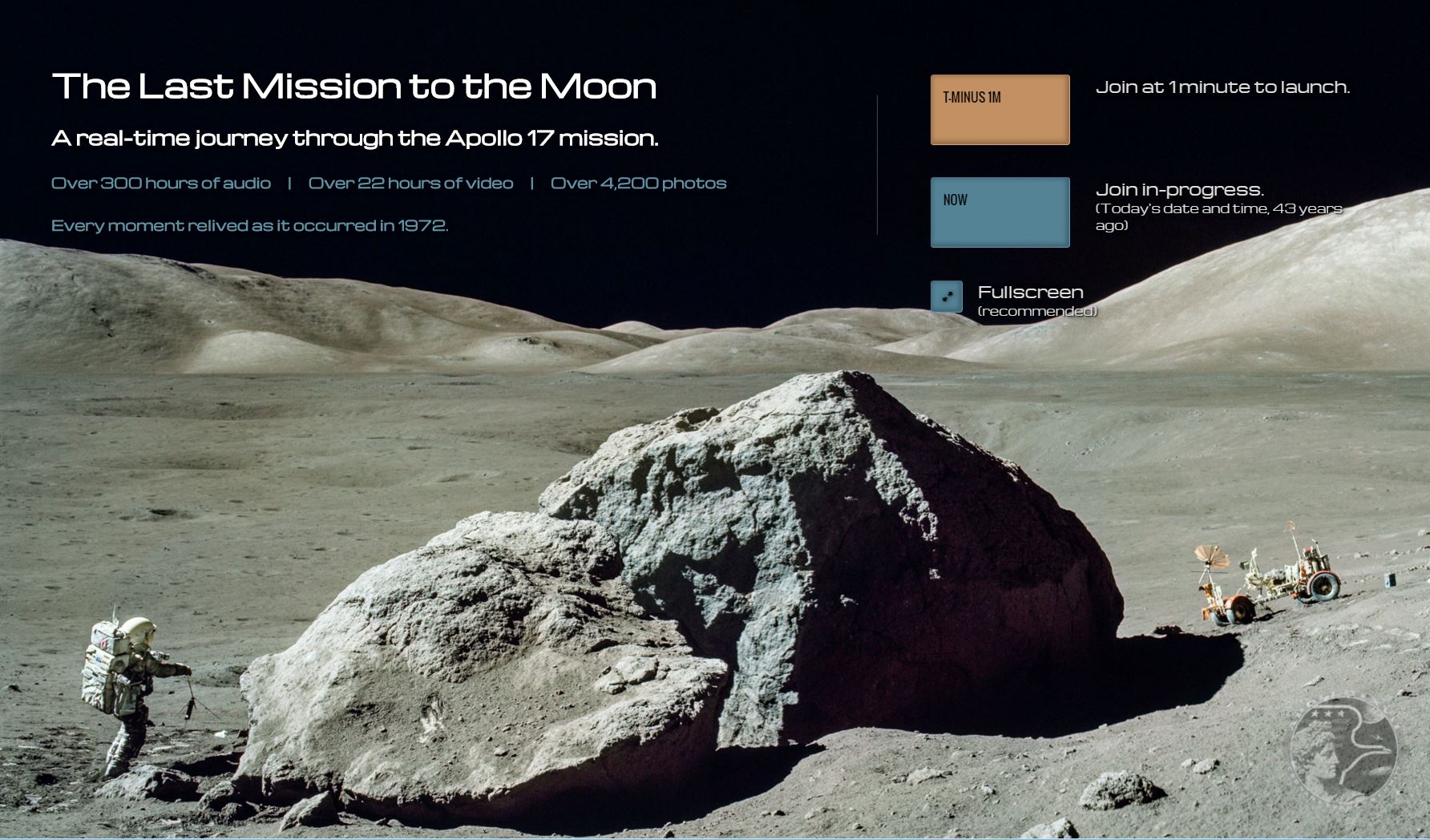

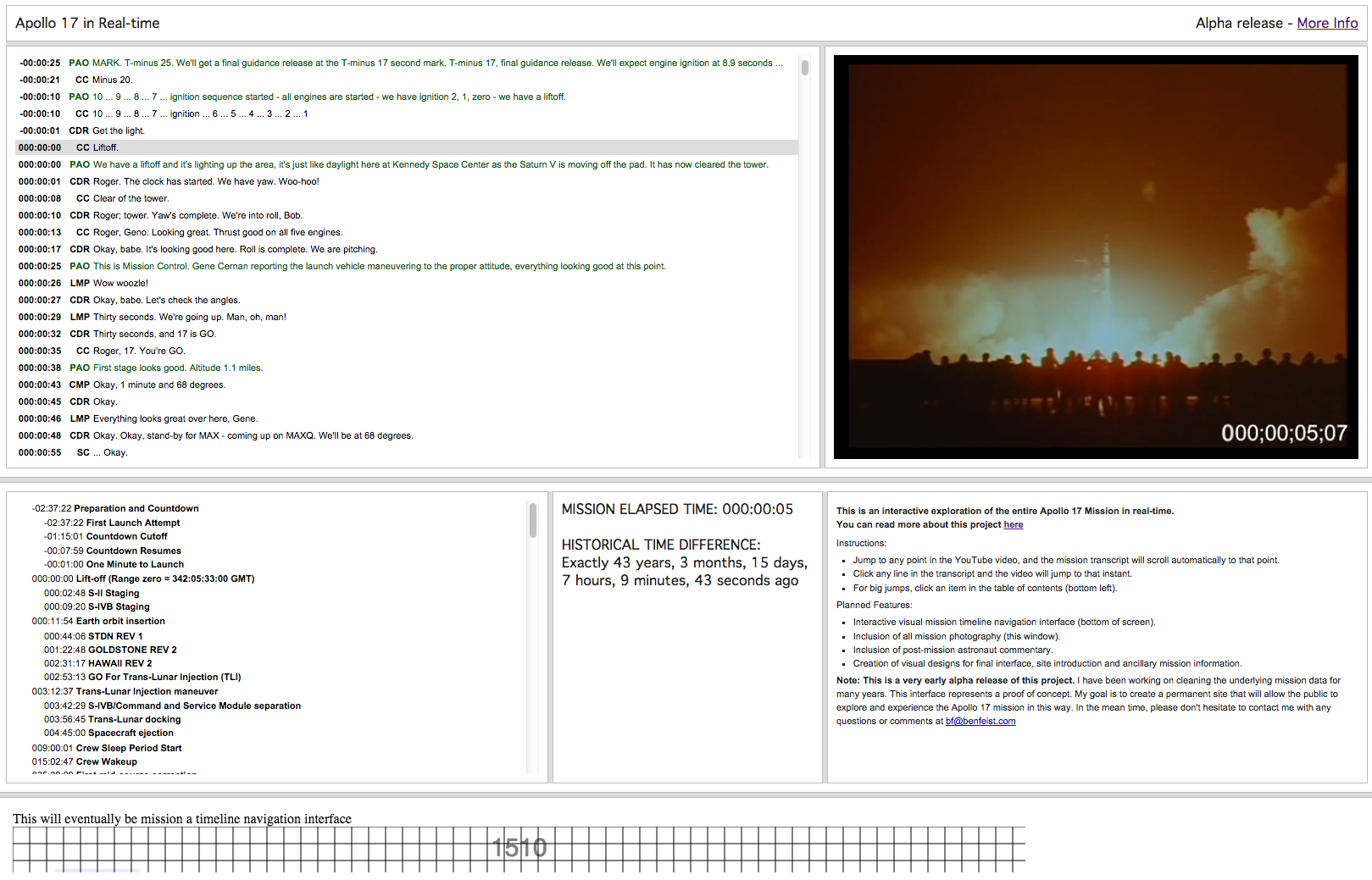

Creation of Apollo17.org, a real-time digital experience of the Apollo 17 mission, highlighting design shifts, technical innovations, and archival efforts. Celebrates the site’s acclaim from NASA, Apollo 17 crew members, and space enthusiasts as a living tribute to the mission’s legacy.

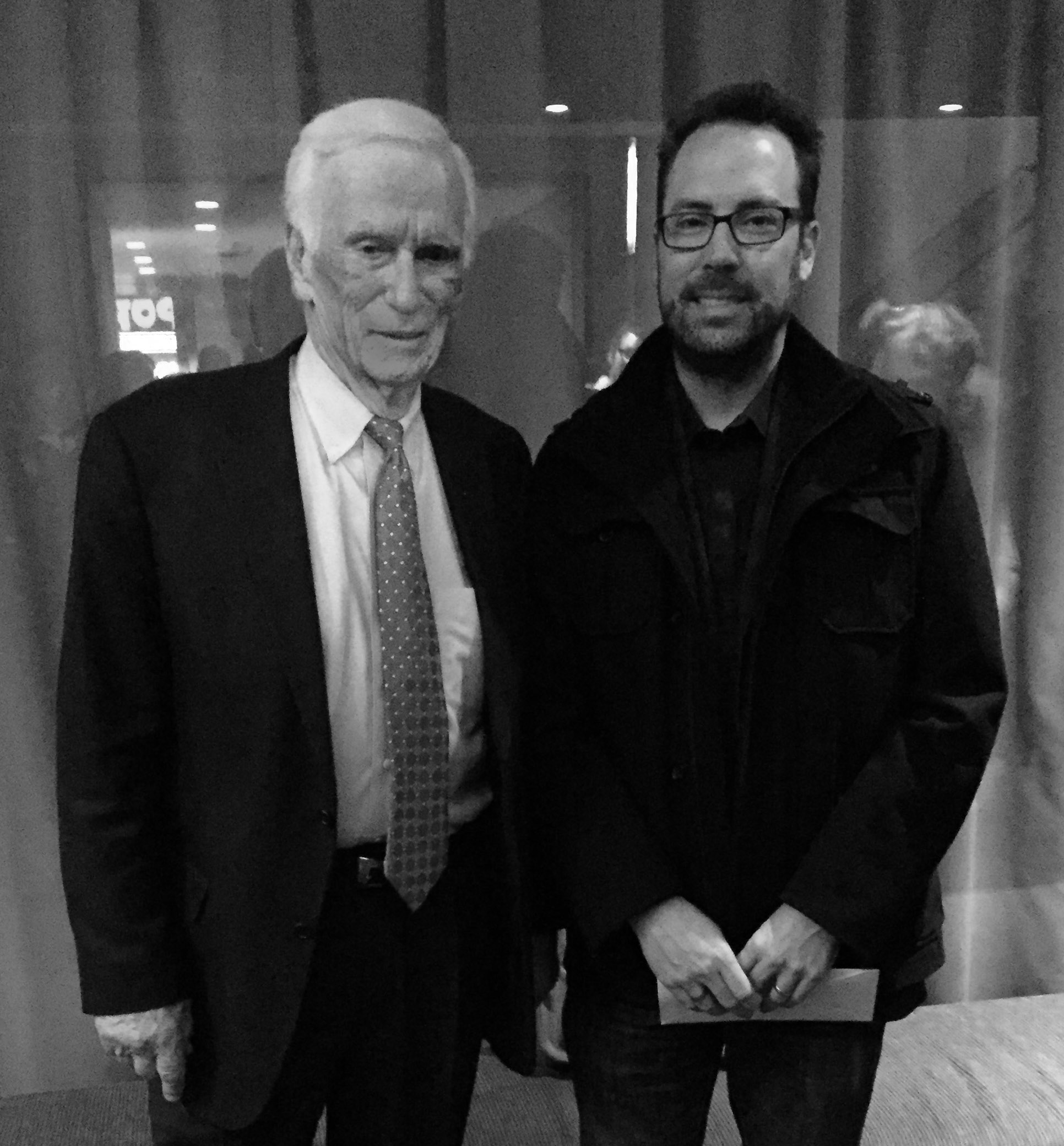

Development of apollo17.org, a real-time simulation of the Apollo 17 mission, highlighting its milestones and future goals. Shares the author’s experience meeting Commander Gene Cernan and discusses plans for enhancing the site’s design, functionality, and historical engagement.

Alpha release of Apollo17.org and the process of digitizing Apollo 17 mission data. This initial release offers an interactive platform for users to explore mission details in real-time.

Update on the Apollo 17 mission audio project and the creation of a YouTube channel containing complete mission videos.