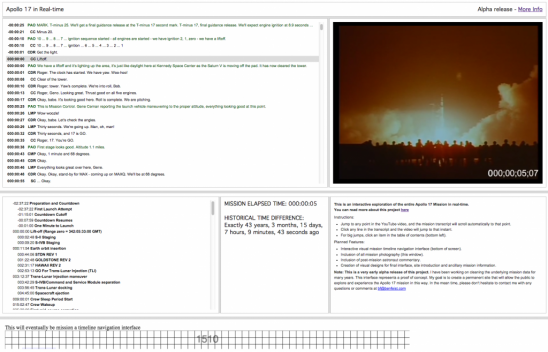

As of this week, I start a new career as a consultant to NASA as an independent contractor. It has been two years since my last update here and, obviously, a lot has happened. The last update, from Fall of 2016, described how I used data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to expand the historical experience of Apollo17.org. This work lead to Dr. Noah Petro of Goddard Space Flight Center, who is now the Lead Scientist on the LRO mission, to invite me to come to Goddard to give a talk during the 44th anniversary of the Apollo 17 mission in December of 2016. This was a dream come true, and I said “yes” on the spot. After so many years of working in isolation on what was ultimately a personal passion project, I was being given the opportunity to visit NASA and explain what I had done with the historical material and the unique use I had found for LRO data.

The presentation was to a room full of Goddard staffers, plus a few retired engineers and scientists who had worked on Apollo 17 itself. I drew upon my experience speaking to senior clients in the software development sector, and gave the presentation my all. I summoned all of my energy to deliver the best “client pitch” I could. I wasn’t selling anything, but, if NASA was inviting me to talk, I was putting my best foot forward. It felt like a victory lap of sorts. By then I had been working on Apollo 17 for 6 or 7 years, and 2016 marked the second major release of the website. This trip to NASA was the perfect end–the cherry on the cake. I could be “finished” apollo17.org and move onto something else. The talk was met with enthusiastic questions and congratulations from everyone. Dr. Jacob Bleacher, Volcanologist and Lead Exploration Scientist for NASA Goddard, was in the audience and asked how difficult it would be to add information about the lunar samples collected throughout the mission. We discussed it and I promised to put it at the top of my list (I added it within a few weeks of my return home). It’s difficult to put into words how rewarding that talk felt. Afterwards, Noah took me to the NASA cafeteria for lunch and, of course, we had to hit the gift shop. I felt great (as I usually do after a presentation, whether it went well or not). Apollo 17 was finished and I would have a story to tell my grand-kids.

Noah checked the time and asked if we could finish lunch quickly. He had to get back to his office for a meeting. Walking back to his building I asked if there was a meeting room I could use to check email while he was busy. Noah’s response was, “No no, the meeting is with you. Some people want to meet you, and just so you know…these people are serious people.” Uh-oh. In came Jacob Bleacher and Dr. Patrick Whelley, a Planetary Geologist who specializes in using point cloud data to conduct geological research. In the discussion, Jacob said that NASA had been looking for the solution to a problem for a long time, and that I may have inadvertently solved it. In a nutshell, the problem is that when astronauts conduct scientific exploration on other planets in the future, the amount of data they will have to collect, organize, and analyze in near-real time will have greatly proliferated since the Apollo era. Today, while on analog missions—where astronauts conduct field experiments on Earth in order to learn how to do the same on other planets—this data proliferation problem is already nearly overwhelming. It takes days or even weeks to pull together all of the field instrument data—camera feeds, audio transmissions, LiDAR point clouds, aerial imagery, hyper-spectral imagery, handheld spectrometer data, Schmidt hammer readings, etc.–into a process that allows the team to analyze it all together. Jacob explained that organizing and visualizing field data the way I had for Apollo17.org could be the answer to this problem. I didn’t really know what to make of this. I think I stammered something about being glad that I could help—that I was glad that my idea could help them to find a way to solve the problem. Jacob said, “We’re not going do solve it. You are.” Jacob and Patrick invited me to join them in the Potrillo volcano field in New Mexico the following June on one of their analog missions.

Myself, and astronaut, Harrison H. (Jack) Schmitt at the Apollo 17 45th Anniversary Symposium, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

A few weeks later, Noah invited me to return to Goddard in March of 2017 to give a talk at the Apollo 17 45th Anniversary Symposium. At the Symposium, I would be the first to speak after Jack Schmitt, Lunar Module Pilot on Apollo 17, who’s voice I had listened to painstakingly for so many years while building Apollo17.org. Jack spoke about his journey to the Moon and the continuing scientific research on the geology of the lunar valley he explored in 1972. Giving that talk was like having an out-of-body-experience. Jack was sitting in the front row of a room that seated several hundred NASA scientists (who had all come to hear Jack’s talk, not mine). For an hour, I took this remarkable opportunity to tell Jack (and the rest of the audience) the detail of all of the work I had done to bring his mission back to life and restore it for posterity. I kept getting tongue tied between saying things like ‘when the crew did such in such’; switching to saying to Jack, ‘when you did such in such’. I was talking to the last surviving member of the crew who actually did these things. Jack was very gracious and congratulatory afterwards and took the time to shake my hand in front of the audience saying, “Thanks for the great work and keep up being a hobbyist.” I think he may have taken exception that it took a volunteer effort to do what he thought NASA should have been doing to begin with.

Astronaut Barry “Butch” Willmore, Astronaut Jack Schmitt, discuss field geology with Prof. Jose Hurtado. Jacob Bleacher in background (black hat).

On that first day at Goddard when Jacob and Patrick had invited me to join them in the Potrillo volcano field in New Mexico, I had no scientific training, no field experience, had no idea how I would get the time off work, and was filled with self-doubt about whether I could deliver anything of value to NASA. I said “yes” on the spot. I would be with field geologists and other scientists from across NASA centers and educational institutions, and Barry “Butch” Wilmore, an active NASA astronaut, former Navy F18 pilot, shuttle pilot, and commander of the International Space Station. Also, I learned later, Jack Schmitt, at the age of 82 would be joining us in the field as well. My job was to observe and look for ways to help the team to gather their data in a way that would enable it to be temporally organized and visualized later. I met many fantastic people on that trip. I was made on honorary member of “team LiDAR” where Patrick and Jacob Richardson, a planetary volanologist, focus their energy. I learned as much as I could about how LiDAR was being used to analyze geological formations. I helped to carry LiDAR equipment through the desert where I became very familiar with a particular black tripod. Kelsey Young, a planetary exploration scientist who was running the X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) hand-held instrument, took me under her wing and had infinite patience, energy, and detail while answering my less-than-undergrad geology questions. One need only spend a few minutes with Kelsey to agree that she should be the first person to walk on Mars. Spending time with Jack Schmitt in the field was surreal. We were covering the very ground he had covered with other Apollo astronauts back in the 60s while training them on how to conduct field geology. One day in the field, Butch Wilmore, after having learned of my unusual background story, said to me, “Ben, I want to get your story straight. You did all of that work on Apollo 17 on your own time?”

“Yep”, I said.

“And then NASA called you?” Butch asked.

“Yep”, I said.

“And now you’re out here with us in the desert?” Butch asked again. Before I could answer, and not realizing that Jack was right behind me, Jack said to Butch, “He’s a little bit crazy, but we don’t say that when he’s around.” I had just been burned by an Apollo astronaut.

The details of what I was specifically doing on this trip is covered in this article by Katherine Wright, a journalist who was with us in the field.

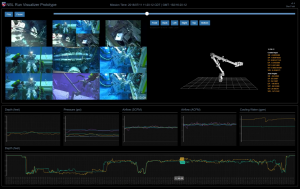

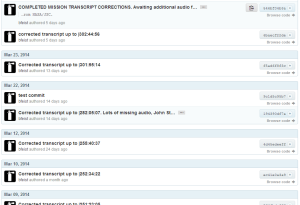

Everything up to this point took place between that first visit to Goddard in December of 2016 and June of 2017. Over the summer of 2017, my interactions with people at NASA was cooling down. Jacob and the people I met in the field were off on other deployments and I was out of sight and out of mind. My phone could have easily stopped ringing. I realized that there was nothing stopping me from taking a crack at building out a software solution using the field data we had gathered. I had all of the data, and this wasn’t like the private sector where I had spent my career–where I could depend upon having a client with a very particular idea of what they wanted and who wouldn’t accept anything else. Jake included me in order to help solve a problem, not to build something he already had in mind. So, with this in mind, I hacked together a prototype that pulled all of the data for one of the analog extravehicular activities (EVAs, aka spacewalks) into a navigable visualization. I worked on this over the rest of the summer of 2017 on evenings and weekends, not hearing too much from Jacob and the rest of the field team over that summer.

When the prototype began to resemble something showable, I sent it over to Jacob and team for feedback. Immediately, I heard back from Jacob. He thought it did a great job of capturing what his field analogs were all about, and that it was an excellent first step in illustrating the form that a data analysis tool could take. I packaged it up for Jacob and Noah to use at the American Geophysical Union conference in the fall of 2017. My little prototype had grown legs and the phone kept ringing. I joined Jacob and team back at Potrillo in 2018 for a second run at gathering scientific data in the same area to ultimately unravel the geological mystery of how the volcano at Kilbourne Hole formed. At one point, Jacob pointed out that I have more field experience that half of the planetary geology community. I said, “Yes, but I have more field experience than 99.9% of the computer science community.”

While at the Potrillo analogs, among the many people I met was Dr. Paul Niles, Assistant Chief Scientist at Johnson Space Center (JSC) who works in the Astromaterials Research in Exploration Science (ARES) group. After learning about my novel approach to data organization and visualization, he thought there could be many programs at JSC interested in benefiting from it. He began discussions within JSC and gathered a broader team of scientists and management to take the idea forward. The first group that took an interest was the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL). This is the enormous indoor pool where astronauts learn how to conduct spacewalks on a full-scale mockup of the International Space Station under 40 feet of water. Cool! The NBL had recently realized that they would benefit from a system that would allow them to navigate data from across systems allowing them revisit moments on completed training runs. Paul described my efforts to them and they were immediately interested in having me pull together a prototype using NBL data. I had no idea how I was going to approach this, but I gave an enthusiastic “yes”!

In winter of 2018, Noah suggested that I write an application to be a speaker at LPSC. I said “Sounds great. …what’s LPSC?” I came to understand that LPSC was the 49th annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, where planetary scientists meet once per year to present their scientific research to large auditoriums full of their peers. My talk was titled DOCUMENTING OF GEOLOGIC FIELD ACTIVITIES IN REAL-TIME IN FOUR DIMENSIONS: APOLLO 17 AS A CASE STUDY FOR TERRESTRIAL ANALOGUES AND FUTURE EXPLORATION and was the scientific version of this blog post. I felt that I could confidently speak about my work, but then learned that the talk would be in front of 500 people, could be no longer than 12 minutes, and must leave 3 minutes for a potentially excruciating Q&A. I timed myself in my hotel room and discovered that I had far too much material in my presentation. After taking a hatchet to the content, I stood in front of a room containing hundreds of PhDs, with Jack Schmitt, Gerry Griffin, Jacob Bleacher, and Noah Petro sitting in the front row. No pressure. The talk focused on how a single tool could be made that enabled scientific research and could also ignite the imagination of the general public. I have very little memory of the talk itself, but was later told that I did well. Afterwards, it became apparent that I had made many new friends during that 12 minutes. Mission planners, planetary scientists, senior NASA officials, and members of the press were all interested in hearing more, and was happy to speak with anyone who would listen.

When I returned home, I received the NBL training data that I was to visualize. Once again, I worked over evenings and weekends to make a prototype visualization. This time, I recruited my father to help. My father, Harold Feist, is both, an artist and a coder. He has made his living painting large abstract paintings since 1976, and somewhere around 1984 took an interest in programming as well. It was from him that I learned how to code creatively—to focus on the display aspects of what you make and to use code as a medium. This is what multimedia projects are all about. Nobody uses the term “multimedia” anymore, but there’s no more apt description of apollo17.org and these subsequent prototypes. For the NBL prototype, my father built out a 3D webGL display of the Canadarm2 (an underwater, robotic mockup of the Canadarm2 is used during the NBL training runs) allowing the user to see the arm orientation at any given point of the training run. I integrated this into the rest of the NBL prototype and sent it down to Paul at JSC. When Paul and the rest of the team presented it to senior NBL leadership, it was met with universal enthusiasm. One person even suggested that having such a system could reduce the overall risk factors that the astronauts face when training under water. That sounded like a major win to me.

Throughout these past few years I have struck up a personal friendship with both Noah and Jacob. Noah has never failed to provide encouragement and guidance. For the first many years of this adventure, Noah was my only contact within NASA. He repeatedly found ways to keep me engaged. He invited me to talks, kept his ears open for any conversations at NASA HQ or Goddard that he thought could benefit from my input, flew me down on several occasions to be involved; the list goes on and on. Jacob is entirely responsible for seeing the potential of what I had built and how it could be applied broadly at NASA. He would never hesitate to bring forward suggestions that would make my work better or to help move the ball down the field. I, of course, had no ability to enable my idea within NASA. It was Noah, Jacob, Paul, and may others who did that. It goes without saying that I am eternally grateful to them for their continuing support.

Throughout this adventure, every time I met someone new or had a new conversation, I would try to find a way to add value—to help. Don’t ask for things; offer things. This stance culminated in a phone call from Noah and Jacob this past fall asking if I would be interested in working on NASA projects full-time. Jacob said, “Your name is on so many things for 2019 it would be easier if you just worked here.” Once I had regained my composure, I responded, “Yes.”

I’m writing this on a flight back from Houston after a week at JSC. With the help and support of Paul and many others who I haven’t included in this article, I have become a consultant to NASA as an independent contractor under the Jacobs/JETS contract, splitting my time between JSC and Goddard. I will be working on a wide variety of computer science projects, and will be continuing my work on Apollo history. All of this will center around visualizing cross-disciplinary operational and scientific data in real time. I’m sure I’ll get the opportunity to apply myself to many other crazily interesting projects. Whatever is thrown my way will be met with an enthusiastic “yes.”