As discussed in my previous post, The Apollo 17 PDFs contained an early attempt at recognizing the typewritten text using Adobe Acrobat’s built in OCR functionality. Working from Adobe’s OCR output would result in a huge amount of manual labour, which kind of defeats the purpose of using OCR to being with.

I did some research and found that ABBYY FineReader 11 offered many interesting features that I could use to digitally extract the transcript data into a format I could use for further processing with Python cleanup scripts (I’ll cover that cleanup step in a later post). The key feature that made me select FineReader was its ability to detect patterns in a page and create table grids that would compartmentalize the data recognized into regions. This auto-detection was only about 80% accurate, requiring manual intervention on almost every page of the transcript but it was the best combination of automation and manual labour to get a result that was free of the issues in the PDF and could be manipulated further.

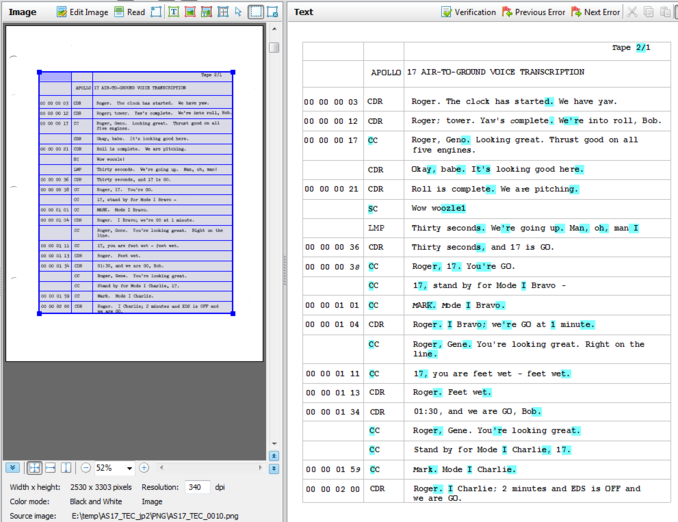

In the screenshot above you can see the grid I established for the first page of the transcript. This grid breaks up the timecode, speaker, and verbiage data into three separate table columns. It also breaks each event into its own table row. Establishing the rows also has the benefit of allowing wrapped verbiage data to remain in the verbiage column without disrupting the timestamp data. The right side of the screenshot is the resulting OCR output from FineReader. Characters that are highlighted in cyan are considered “maybe” characters by FineReader. Theoretically, if I trained FineReader to understand these maybe occurrances it would be more accurate on subsequent pages. I spent much time training and retraining but never found that there was any benefit. I knew that later I would have to read through manually anyway, but this step wasn’t the time to do so.

In the screenshot above you can see the grid I established for the first page of the transcript. This grid breaks up the timecode, speaker, and verbiage data into three separate table columns. It also breaks each event into its own table row. Establishing the rows also has the benefit of allowing wrapped verbiage data to remain in the verbiage column without disrupting the timestamp data. The right side of the screenshot is the resulting OCR output from FineReader. Characters that are highlighted in cyan are considered “maybe” characters by FineReader. Theoretically, if I trained FineReader to understand these maybe occurrances it would be more accurate on subsequent pages. I spent much time training and retraining but never found that there was any benefit. I knew that later I would have to read through manually anyway, but this step wasn’t the time to do so.

This step lasted a few weeks. Each evening after work I put on some tunes and carefully establish this grid for every page of the transcript. Some of the pages were scanned at a 5 – 10 degree angle whiched cause FineReader to completely panic and interpret the entire page as garbage. This only happened 10 – 15 times though. Those pages will have to be re-keyed at a later stage.

Digital Output

Another great feature of FineReader it to output table results directly to Excel. This would allow me to perform the first steps of the testing and scrubbing of the output data. Here’s a link to the first 500 pages of the TEC transcript as directly outputted by FineReader if you’re interested. You’ll notice that the original Tape numbers are contained in the output. This was done deliberately in order to be able to refer back to the original typewritten page from any point in the transcript.

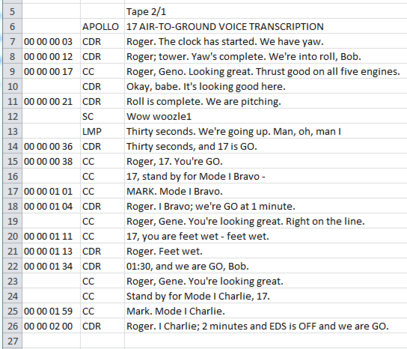

In the screen grab above you can see that within Excel the transcript is intact. Timestamp, speaker, and verbiage are in three columns and the lines that were wrapped in the typewritten transcript are no longer wrapped. I should point out that this didn’t “just work”. I had made errors in tabling some of the pages resulting in big mistakes in the output. Looking at the column sizes in Excel helped me to discover these errors and correct them in FineReader before outputting again–and again. I was careful to not manually make any changes to the resulting CSV (Excel) output. This was important because I wanted to ensure that if I had an insight somewhere down the line about additional OCR cleaning, then I still had the option of doing something differently in FineReader and just generating the output again. If I had tampered with the output then any new output from FineReader would overwrite my manual changes.

In the screen grab above you can see that within Excel the transcript is intact. Timestamp, speaker, and verbiage are in three columns and the lines that were wrapped in the typewritten transcript are no longer wrapped. I should point out that this didn’t “just work”. I had made errors in tabling some of the pages resulting in big mistakes in the output. Looking at the column sizes in Excel helped me to discover these errors and correct them in FineReader before outputting again–and again. I was careful to not manually make any changes to the resulting CSV (Excel) output. This was important because I wanted to ensure that if I had an insight somewhere down the line about additional OCR cleaning, then I still had the option of doing something differently in FineReader and just generating the output again. If I had tampered with the output then any new output from FineReader would overwrite my manual changes.

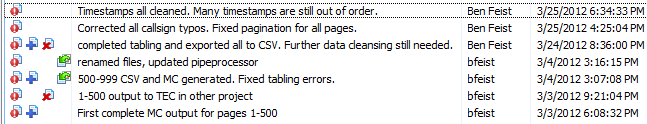

In this screenshot you can see the number of large milestones that were hit in the main effort to get clean CSV output from FineReader

The timestamps originally came out as all manner of different characters, not only digits. This and many other problems were to be cleaned in the next step, Python processing of the CSV output, which I will cover in a future post.