When tabling and OCRing all of the transcript pages, running python cleanup procedures and manually running search and replace rules, I had a lot of time to think about this project and where it might lead. The underlying thought that I kept coming back to is that I’m re-establishing a cohesive chain of events that occurred over a 13 day period, 40 years ago. Starting from this idea of a chain I expanded my investigation to include other media elements in addition to the transcript. I realized that I would have to reconcile all of the audio recorded, film shot, photos taken, and television broadcast during that 13 day period in order to reconstruct the chain of events.

When tabling and OCRing all of the transcript pages, running python cleanup procedures and manually running search and replace rules, I had a lot of time to think about this project and where it might lead. The underlying thought that I kept coming back to is that I’m re-establishing a cohesive chain of events that occurred over a 13 day period, 40 years ago. Starting from this idea of a chain I expanded my investigation to include other media elements in addition to the transcript. I realized that I would have to reconcile all of the audio recorded, film shot, photos taken, and television broadcast during that 13 day period in order to reconstruct the chain of events.

Audio Analysis

The Internet Archive contains digitized copies of many of the original Apollo 17 tapes in their entirety. This audio is incredibly raw. Some of the tapes were even digitized backwards (easily rectified with software). The audio is provided in enormous lossless WAV files, each several gigabytes in size. This makes the audio difficult to work with given that I need to be able to play with all of it at once. The first step was to convert all of these WAV files into high quality MP3. With MP3 encoding on its highest variable bitrate setting the quality loss is completely negligible. The recordings contain a very narrow audio frequency band and much of the data in the WAV file was superfluous anyway. As MP3s the audio files were reduced to a couple hundred megabytes in size each, much easier to work with from a memory and disk access point of view.

The Internet Archive contains digitized copies of many of the original Apollo 17 tapes in their entirety. This audio is incredibly raw. Some of the tapes were even digitized backwards (easily rectified with software). The audio is provided in enormous lossless WAV files, each several gigabytes in size. This makes the audio difficult to work with given that I need to be able to play with all of it at once. The first step was to convert all of these WAV files into high quality MP3. With MP3 encoding on its highest variable bitrate setting the quality loss is completely negligible. The recordings contain a very narrow audio frequency band and much of the data in the WAV file was superfluous anyway. As MP3s the audio files were reduced to a couple hundred megabytes in size each, much easier to work with from a memory and disk access point of view.

Scrubbing through a sampling of the audio recordings exposed a new problem. These were extremely old tapes played through specially restored tape players that were custom built for the original job of recording the missions (more info here). These old tapes obviously had no timecode embedded within them as modern tapes do. When these tapes were originally recorded there were subtle variations in the tape speed due to the analogue nature of the system. Again when played back, the repaired machines could have been playing slightly fast or slightly slow, or variably as a tape played. The only thing to go by is the human ear, and paying attention to the content to see if things sound right (although over many hours much of the audio just sounds like this (WAV)). You can also go by the times when the PAO officer announces the Ground Elapsed Time (GET), usually every time he speaks, but he only mentions the minutes, not the seconds. Over hundreds of hours of audio, the variation that all of this introduces has to be solved one way or another.

Scrubbing through a sampling of the audio recordings exposed a new problem. These were extremely old tapes played through specially restored tape players that were custom built for the original job of recording the missions (more info here). These old tapes obviously had no timecode embedded within them as modern tapes do. When these tapes were originally recorded there were subtle variations in the tape speed due to the analogue nature of the system. Again when played back, the repaired machines could have been playing slightly fast or slightly slow, or variably as a tape played. The only thing to go by is the human ear, and paying attention to the content to see if things sound right (although over many hours much of the audio just sounds like this (WAV)). You can also go by the times when the PAO officer announces the Ground Elapsed Time (GET), usually every time he speaks, but he only mentions the minutes, not the seconds. Over hundreds of hours of audio, the variation that all of this introduces has to be solved one way or another.

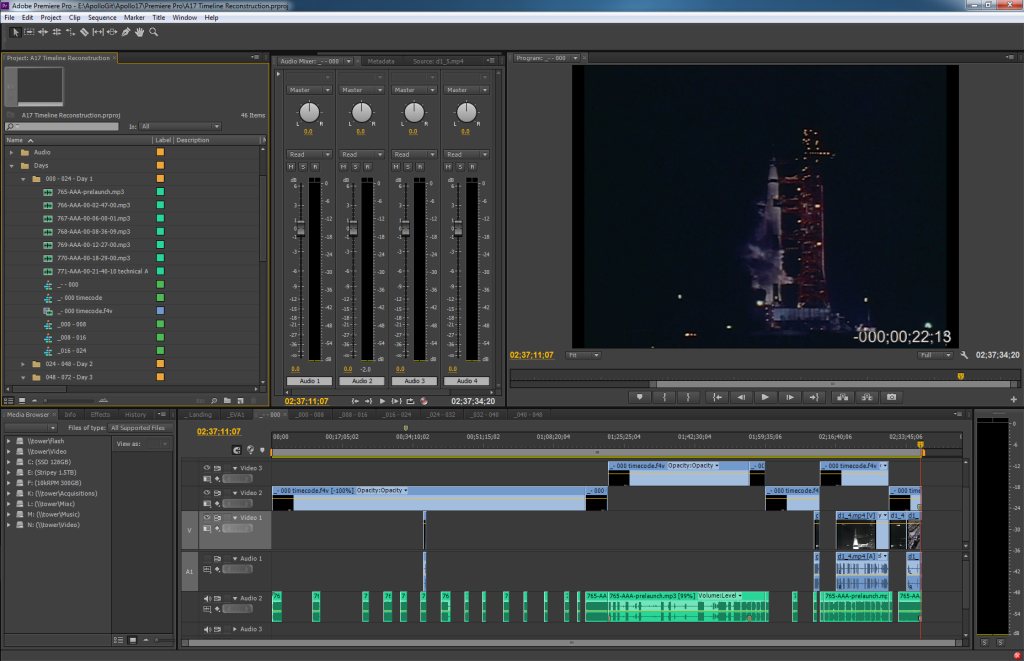

Establishing Base Timeline

I decided to use Adobe Premiere to create a complete 308 hour mission time project in 8 hour segments (8 hours each so that Premiere doesn’t choke on a project of such enormous duration). On these 8 hours segments I would lay all of the mission audio. In the video output I would display a GET timecode in the bottom right that runs at 30FPS for 13 days. This is the foundation of the mission timeline reconstruction. By using Premiere’s ability to accommodate many different source audio and video types I can use it as a kind of scrapbook for the timeline. TV broadcasts, 6FPS 16mm film source, MP3 audio, even imagery could be merged into this Premiere Project.

In the screenshot above you see Adobe Premiere with the prelaunch segment loaded up for display. In this case (because it the time leading up to prelaunch) the segment duration is 2 hours, 37 minutes, 34 seconds, 20 frames long. In the top right is the video preview window, the negative countdown timecode in the bottom right of it. The video footage is original launch coverage footage shot by NASA.

In the screenshot above you see Adobe Premiere with the prelaunch segment loaded up for display. In this case (because it the time leading up to prelaunch) the segment duration is 2 hours, 37 minutes, 34 seconds, 20 frames long. In the top right is the video preview window, the negative countdown timecode in the bottom right of it. The video footage is original launch coverage footage shot by NASA.

Along the bottom of the segment editor you can see how I had to cut up the mission audio to match the times announced by the PAO officer as he provided prelaunch commentary. The dead air was apparently edited out in the PAO recording. I reestablished this dead air. Perhaps later I’ll come across additional mission audio such as the Flight Director audio loop (currently not in the Internet Archive) and will be able to lay it in within the dead air.

There were several countdown holds that occurred, both scheduled and due to problems, so I had to hold and resume the mission timer at the appropriate points. I also found that the audio had to be slowed down 1% in order to get it to better match with the transcript timecodes. This isn’t an exact science. The transcripts are only partially accurate and, as described above, the audio playback speed isn’t authoritative. But I could see that times were trending towards being further and further off from the transcript in general as time passed. A 1% stretch addressed this generally, allowing me to then treat the audio as “on track” and to use the resulting timecode as a source for corrections to the transcript timecodes.

This screenshot shows Premiere with a full 8 hour time segment loaded. This is the first 8 hours from the moment of launch, GET 000:00:00 to 007:59:59:29 (remember, the last digit is out of 30 for 30 FPS). You can see at a glance that a huge amount of mission audio is missing from the Internet Archive (34 minutes after launch to 2 hours, 49 minutes after launch to be exact). These kinds of gaps are called out via this process to be investigated and hopefully filled later. The film footage of docking is from the onboard 16mm film camera that ran at 6FPS I synced this footage with the transcript so you can see the moment of docking right when it occurs. Again, as additional footage and source material surfaces it can be added without messing up the foundation of the project because the foundation is a bare 308 hour timecode.

Tape Within Tape

One confusing point worth mentioning is my discovery that some of the source audio is actually playback of other times within the mission. I was confused for days due to the timestamps suddenly being off by hours against the transcript rather than seconds, before realizing what was going on. This occurred in-the-moment back in 1972 on the PAO loop audio (which is the only source material available to me). For example, in one instance the mission is progressing and the PAO officer announces that an hour-long press briefing will occur in 10 minutes, then the tape cuts omitting the briefing, and resumes with the PAO officer stating that he will play back the air-to-ground events that occurred during the press briefing. What then follows in the recording is an edited down version of the events of that hour with dead air edited out in order for them to catch up to real time. Once they catch up the PAO officer states that they are now “live” again, and the recording continues. To reconcile these segments I bounce back and forth between the TEC transcript and the recordings to reconstruct what occurred in that hour, moving the replayed bits back into place on the timeline doing my best to reestablish the edited out dead air.

Sleep periods are another source of dead air and missing audio. The Internet Archive material has hours of presumably dead air edited out of some of their recordings with the occasional announcement by the PAO officer, who thankfully states the GET time when he speaks. This sleep time is left in real time in my project. In the future if there is recovered ground operations data it would be interesting to discover what mission control was working on and saying on the Flight Controller loop while the crew was asleep. We won’t know unless the material is somewhere in the NASA tape archives.

The First 48 Hours

As of now, December 19, 2012, I have placed the audio and video I have available onto the time timeline for the first 48 hours of the mission. This took quite some time but was an interesting and personally rewarding way to discover the content within the source material. I’ve decided to pause this timeline effort in order to move on to the original purpose of all of this, namely correcting the TEC mission transcripts via the original timeline audio.

Pingback: Ben Feist